Their celebrations are only two days apart, and St. Patrick and St. Joseph have something in common—one worked for Jesus, the other raised him.

We know much about St. Patrick. He was a Roman by descent, he converted Ireland to Christianity, and he is beloved by that nation. St. Joseph’s story is a little less clear. He was Jewish, a carpenter, and a very accepting stepfather. More on that later.

Both saints are venerated with food. I don’t know why St. Patrick’s Day calls for corned beef and cabbage; but prayers to St. Joseph are credited with saving the crops in Sicily during the Middle Ages hence the food fest known as the St. Joseph’s Table.

Because it is mainly a Sicilian custom, my Neapolitan (Campania Region) family never hosted a Table. But the two regions managed to come together with their own versions of St. Joseph pastry: the Neapolitan zeppole and the Sicilian sfinge. Both are winners, the former filled with custard, and the latter with cannolo cream.

Beyond the food, each of these saints has a backstory that is somewhat controversial. Even the most devout of Catholics must be aware that one of the reasons Joseph is held in saintly esteem is due to his acceptance of, and marriage to, a pregnant Mary. Mary’s “perpetual virginity” is basic to Catholic doctrine, which challenges Scriptural references to Jesus’s brothers and sisters. Catholics can believe that these were actually close “cousins” or step siblings from Joseph’s previous marriage (no mention of that). Either way, Joseph did not have relations with Mary before or after marriage. Outside of this saintly behavior, Joseph did not perform any miracles during his lifetime or become a Christian martyr.

The same can be said of Patrick. His claim to fame (or sainthood) is for successfully converting the Irish to Christianity, not any miracles or martyrdom. (Driving the snakes out of Ireland is a myth.) The missionary before him, Palladius, was sent to Ireland by Pope Celestine in A.D. 431. Palladius didn’t hit it off well with an Irish warlord and was quickly transferred to Scotland. That’s when Patrick stepped in, around A.D. 432. He was 47-years-old, but knew Gaelic from his youth—he was kidnapped at age 16 from Britain by Irish pirates and enslaved for seven years. He spent almost thirty years spreading the Gospel in Ireland, dying in A.D 467, around 82-years-old.

Don’t imagine that Patrick singlehandedly converted the Irish. He had a staff of missionaries that included names like Auxilius, Secundinus, and Iserninus. Like Patrick, his staff came from Roman provinces and spoke Latin. This is important. As author Thomas Cahill wrote in his peon to the Irish in How the Irish Saved Civilization (1995) “…Christianity cannot be understood apart from Romanization.” Not only were the Irish converted to Catholicism they were Romanized. Patrick had to deal with Irish practices like human sacrifice and even ceremonial buggery (with white mares!) by some Irish kings, according to Cahill.

Romanizing the Irish began even before Patrick. Now well documented, the Romans had an outpost in eastern Ireland at Drumanagh, fifteen miles from Dublin. Archeologists date it as early as A.D. 79 to A.D 138. It only makes sense that the Irish and Romans dealt with each other commercially prior to Patrick. Eventually his Catholic missionaries as well as their converts made Latin a second language among educated Irish.

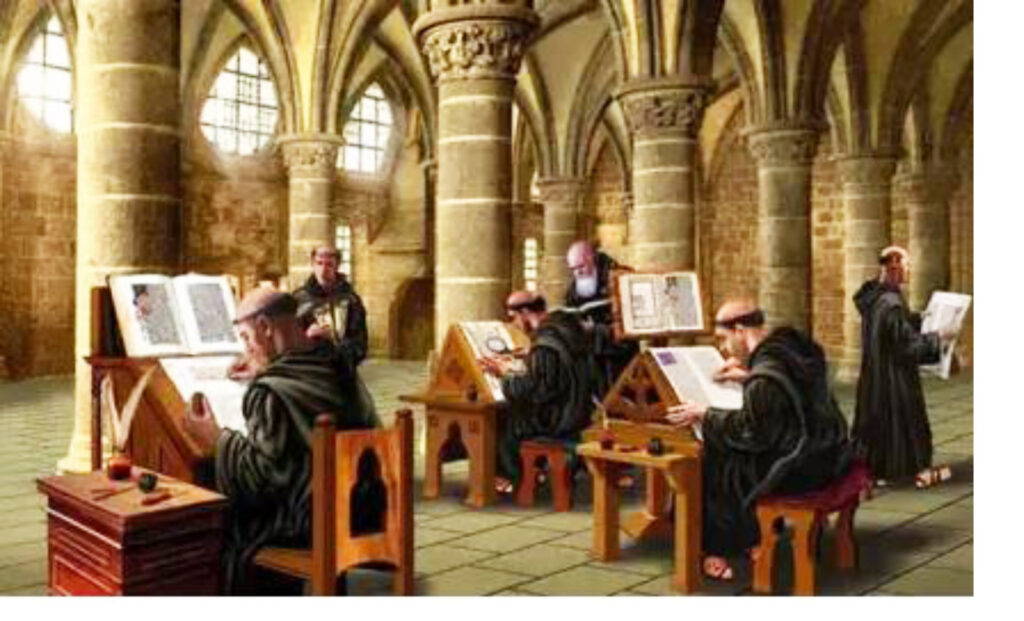

This is exactly how Thomas Cahill explains the manner in which the Irish “saved” civilization. Latin-speaking Irish monks copied Christian and pagan scrolls to preserve and disseminate them in Ireland. With the barbarian invasions across Europe in the A.D. 400s and 500s and the destruction of Roman libraries, the Irish copies were an emergency backup. Of course, Irish monks weren’t the only “saviors,” monks were plentiful on the Continent.

Patrick and Joseph may be part of the community of saints, but some have special worshippers. -JLM

Next to our annual Festa, St Joseph Day brings out the greatest number of participants to our events…as well as volunteers….I grew up with the tradition, from Calabrese roots, and as the tradition was always associated with charities, recalling a lady who every year hosted a St Joseph table to collect funds for an orphanage in the ancestral town of my grandparents.

There is a supportive community component to the event, including free meals, collecting of funds for the poor, and the symbolic fave as a reminder its necessary to grow your food too. You can go online and check out the celebrations in New Orleans where the celebration is still quite vibrant and has become a part of the culture.

Locally attendance has been declining. The demographic spread, blended cultures and intermarriage, all have taken their toll. Perhaps the event has to be repackaged….as a way to promote the wonders of vegetarian cooking since no meat is allowed at the event.

Also, I am no canon law scholar but why is it corn beef is allowed on St Patrick’s Day, and no meat on the St Joseph’s Table? I am fine with it…but could never understand why…..bottom line no one goes away hungry on either Saints Day !. Also in Itlay St Joseph’s Day is Father’s Day, but certainly not celebrated the same as the Festa…..