What was Christopher Nolan thinking?

In directing Oppenheimer, which has garnered 13 Academy Award nominations, Nolan relegates Enrico Fermi — the true architect of the nuclear age — to a bit part.

J. Robert Oppenheimer served as the director of the Manhattan Project’s Los Alamos Laboratory during the development of the atomic bomb, but he did not usher in humanity’s new technological epoch.

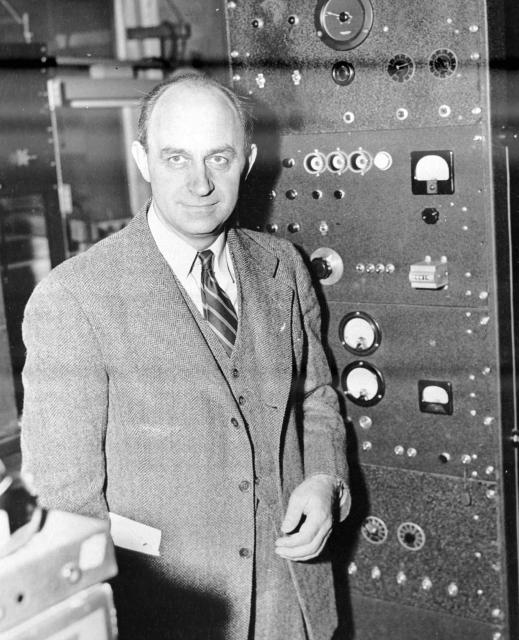

Fermi was the Nobel Prize-winning Italian physicist whose pioneering experiments with uranium caught the attention of Albert Einstein as the winds of war were enveloping Europe.

Ultimately, Fermi created the world’s first nuclear reactor, which led to the advent of nuclear energy and made the Little Man and Fat Boy atomic bombs a reality.

On Dec. 2, 1942, in a converted squash court beneath the stands of the University of Chicago’s Stagg Field, Fermi successfully set off the world’s first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction, a controlled flow of energy derived from a source other than the sun.

Without Fermi, the Manhattan Project would have failed. And no amount of scene-chewing theatrics by Matt Damon as Col. Leslie Groves — nor the enchanting presence of Emily Blunt as the conflicted Mrs. Oppenheimer — can make up for Nolan’s dereliction of filmic duty.

Though the movie depicts Cillian Murphy’s Oppenheimer warmly greeting Fermi in Italian, Danny Deferrari’s Fermi comes across as a not-ready-for prime-time paesano.

In his Aug. 2, 1939, missive to FDR, Albert Einstein wrote: “Some recent work by E. Fermi and L. Szilard, which has been communicated to me in manuscript, leads me to expect that the element uranium may be turned into a new and important source of energy in the immediate future.”

One of the elements whose atom Enrico split was uranium. This work led to his innovative experimentation with neutrons, which led to nuclear fission.

Yet all this is missing from Nolan’s oeuvre. The director also omits any mention of Fermi’s name when referencing Einstein’s famous letter to FDR.

Fermi had been an integral part of the Italian scientific firmament in the 1920s and the 1930s.

In 1933, he developed the pivotal theory of beta decay, which involved the proton, neutron, electron and the “neutrino” — coining the term in Italian as the “little neutral one” and unifying Wolfgang Pauli’s work with Paul Dirac’s positron and Werner Heisenberg’s neutron-proton model.

Fermi was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1938 “for his work with artificial radioactivity produced by neutrons, and for nuclear reactions brought about by slow neutrons.”

Fermi was a Roman Catholic. His wife, Laura Capon, came from a well-respected Jewish family in Rome. Her father Augusto Capon was an admiral in the Italian navy.

According to David N. Schwartz, author of The Last Man Who Knew Everything: The Life and Times of Enrico Fermi, Father of the Nuclear Age: “cultural or political antisemitism was virtually unknown in Italy.” Even the odious racial laws, which were promulgated in 1938 under German pressure, never dimmed the inherent philo-Semitism of the Italian people.

And as Schwartz noted: “True, the fascist regime was repugnant, but the regime never meddled with her husband’s work; indeed, it celebrated that work.”

Moreover, the author revealed that “in deference perhaps to his own ambivalence, Mussolini incorporated an opt-out provision in the racial laws.”

And “Laura’s father, Admiral Capon, applied on behalf of his whole family and his application was accepted in early 1939, meaning that Laura could have returned to Italy at any time during the Mussolini years without endangering herself or her family.”

But things changed “when Mussolini fell in 1943 and the Germans effectively took direct control over much of Italy.” Augusto Capon was later murdered by the Germans in the gas chambers of Auschwitz.

After accepting the Nobel Prize in Stockholm on Dec. 10, 1938, Enrico Fermi and his family later boarded the RMS Franconia in Southampton — and sailed to freedom, arriving in New York on Jan. 2, 1939.

But Enrico had to endure the bigotry of a benighted desk officer who announced the Italian physicist’s presence to U.S. Admiral S.C. Hooper in 1939: “There’s a wop outside.”

Three years later, that same “wop” changed the course of history in a converted squash court in Chicago.

This time, the coded message announcing Fermi (to James B. Conant, head of the National Defense Research Committee) was decidedly different: “The Italian navigator has just landed in the new world.”

As Schwartz averred: “The nuclear age is a broader concept than just simply the nuclear bomb. The nuclear age is, in my view, the moment when man was able to master the process of releasing energy from the nucleus of the atom. Fermi was certainly the father of that.” -RAI

[This opinion was published in the NY Daily News on 9 March 2024]

It’s blatantly singular by now that the woke agenda and politically left and “correct” Hollywood does everything in its power to keep every noble aspect of Italian heritage under wraps. Spielberg’s shameful involvement in the mob cartoon Shark Tale and his dismissal of the outstanding Italic ‘Righteous Gentiles’ over the predicable Nordic Schindler is just another example.

The movie appears to be deliberately trivializing Fermi and his contributions, which are well recognized universally.

The film was about Oppenheimer, not a documentary of the Manhattan Project. Nolan adapted American Prometheus by Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin.

Obviously this is a Hollywood Problem, the movie is not a real movie about Nuclear Physics, it was about politics, as was the OSCARs

What Hollywood is good at, is getting a message out, but the storyline trumps any sort of reality. You may get a “proximity” of reality, and perhaps a curiosity to learn more about the subject, such as in this discussion, but Hollywood does not have much historical credibility. Unfortunately if Hollywood becomes your only history source the damage is done.

As a retired professor from the Department of Energy at the University of Oviedo (Spain), I would like to congratulate you for this interesting and insightful article on E. Fermi.

Professor Iaconis, Thanks so much for the shout out for my book The Last Man Who Knew Everything. Please let me know how best to contact you directly.