A family member recently lamented the current chaos of our times – the political, racial, and sexual polarization in the U.S.– with the following comment: “I’m glad I grew up in the 1950s. Kids were allowed to be kids. You didn’t see this gun violence. Teachers and other authority figures were treated with respect.” When I reminded the relative about the dangers of wearing rose-colored glasses, that the 1950s was also the era of mass conformity, glacial racial progress, lack of opportunities for women, and the Cold War, I was given a stern look: “I meant a sense of innocence.”

Upon reflection, it does make sense, at least from an ethnic standpoint. Why? Because, in the 1950s, Italian Americans were finally coming into their own.

I’m not referring to decades later, when a May 15th, 1983 article in the New York Times Magazine, using that very phrase, heralded how Americans of Italian heritage finally made a triumphant, solid leap into the middle class after decades of struggle.

The author, Stephen A. Hall, highlighted a list of Italian American luminaries in every field as proof: Lido (Lee) Iacocca, savior of Chrysler; Joseph Cardinal Bernardin, Archbishop of Chicago; Eleanor Cutri Smeal, president of NOW (National Organization for Women); Jim Valvano, head basketball coach at North Carolina State; Robert Venturi, architectural giant; Michael Bennett (aka Michael DiFiglia), creator of A Chorus Line and Dreamgirls; Edward DeBartolo Sr., shopping mall magnate; poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti, also owner of San Francisco’s famed City Lights Bookstore; and A. Bartlett Giamatti, president of Yale University.

And more was yet to come in the next decade or so: Geraldine Ferraro (first female VP candidate on a major ticket); Antonin Scalia (first Supreme Court Justice); and New York governor Mario Cuomo (first Italian American politician considered a serious presidential contender).

There had been heroes and heroines before, of course, like Joltin’ Joe DiMaggio (baseball) and Mother Francis Xavier Cabrini (first American saint of the Catholic Church). The 1983 article was clearly meant to show how even further up the scale Italian Americans had gone, economically and socially.

But: What about culturally?

Other than Louis Prima injecting Italian phrases into popular songs during the early years of WWII, Americans weren’t allowed much access to italianità. Even pizza was still largely a mystery, limited to a few East Coast cities.

Ironically, as Italian Americans assimilated and ascended in the 1980s, our cultural legacy actually shrank. We know the reason why: With one single movie, Mario Puzo and Francis Ford Coppola institutionalized the long-held stereotype of the Italian-American-as-gangster. It was an image which the famed American journalist Harry Golden Sr. openly challenged in the 1950s as “not only unfair, but untrue.” Alas, not many people listened to Golden.

And, in an even more bitter irony, it was in that very decade, the 1950s, when Italian Americans were making genuine cultural progress in America.

It began after Italian American soldiers returned from WWII, where they ably proved their valor (over 13 Medal of Honor winners, the largest among any ethnic group). That new-fangled 1950s invention, television, was dominated by Italian American entertainers like Frank Sinatra and Perry Como. It was the same in radio (its forerunner ‘wireless telegraphy’ invented by an Italian: Guglielmo Marconi), which featured pop singers like Tony Bennett, Dean Martin, Julius LaRosa, Connie Francis, et. al. Early rock-and-roll benefitted from producers like Cosimo Matassa (the New Orleans sound) and Frank Guida (the ‘house party’ sound). The aforementioned Lawrence Ferlinghetti and fellow poets like Diane DiPrima and Gregory Corso infused Italian themes and phrases into the Beat Poetry literary movement.

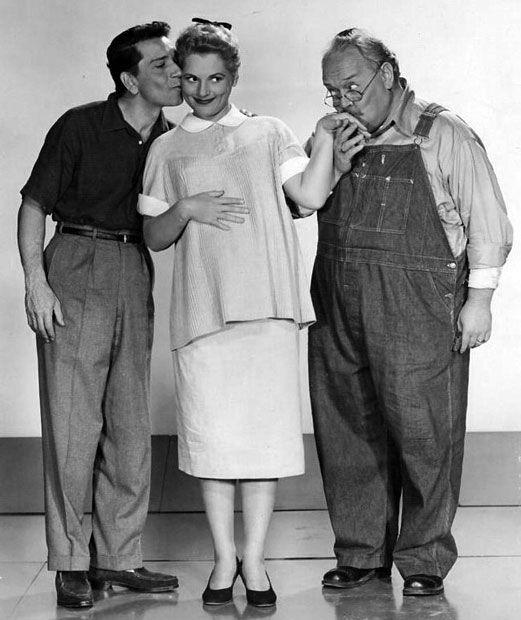

Salvatore Baccoloni in Full of Life (1956)

And the movies! It was the era of Marty (1955), with Ernest Borgnine winning an Oscar for his role as the lonely Bronx butcher. There was Pier Angeli as an Italian war bride in Teresa (1951). Gene Kelly, an Irish-American, played an Italian American seeking justice for the mob-inflicted killing of his lawyer-father in The Black Hand (1950). Colorado-born author John Fante was given the green-light to produce a screenplay based on his own work: Full of Life (1956), with Richard Conte and Judy Holliday as a young couple navigating pregnancy, middle-class suburbia, and Conte’s Italian immigrant parents.

And Tennessee Williams, America’s greatest playwright, wrote not one but THREE works specific to Italian Americans in the South – two plays for Anna Magnani, The Rose Tattoo (1955, which won her an Academy Award) and The Fugitive Kind (1957), and an original screenplay for director Elia Kazan, Baby Doll (1956, featuring Eli Wallach as a Sicilian American at odds with a neighbor over both farm land and a young child-bride).

But then came the beginning of the end: the popular 1959 TV series The Untouchables, which revived the 1920s gangster image. In fact, the show did so very unfairly: many of the fictionalized criminals in the show were automatically given Italian surnames, leading some pundits to refer to the series as “Cops and Wops.” Public protests by some Italian American groups did leave its mark on the producers, who added more positive Italian characters.

But whatever progress was made was quickly upended only a few years later: In 1963, mobster Joe Valachi “sang” in front of a Congressional panel, telling tales of a “secret society” with arcane blood rituals. And he used an Italian phrase which the FBI soon turned into a national mantra: la cosa nostra (“our thing”).

At the time, no one seemed to ask two basic questions: a) how did Joe Valachi, a two-bit hoodlum, know the goings-on of hoodlums much higher up on the food chain? and, b) didn’t other ethnic gangs, such as the Japanese Yakuza, also partake in blood rituals and have “exotic” names for their peeps?

Then came Mario Puzo and his tag-team partner, Francis Ford Coppola, who completed the cultural coup-de-grace in 1972, turning prejudice into “art.”

We’ve gone from the 1950s, which were “full of life” (that is, Italian American culture being allowed to breathe and expand), to 2022, which is now “full of death” (Italian Americans limited to killer roles or to characters who are either intellectually or morally dead). The only positive which non-Italians associate with our culture is food-related. Or, to use a phrase coined by IIA founder John Mancini, “cooks and crooks.” Our full menu has become antipasti.

The 1950s clearly was a more innocent time for Italian Americans. Authors, news editors, filmmakers, great playwrights and even regular Americans saw something of value in our culture. People were open to hearing our stories. Stereotypes were disappearing. The world was literally our oyster.

It’s time to remove the brine. The salt has turned into “saltiness” (disrespect).

To quote that great philosopher, Yogi Berra: “The future ain’t what it used to be.”

Indeed, the past was even better. -BDC

Bill, I cannot help but agree with you, but 100%. We have been pushed aside as I refer to it. The 1950’s and so were a great time to live in this country, city and state of New York, more specifically for me. One could walk the street going from a midnight Mass at the age of 10 to his grandparents and with safety! Imagine that!

Again, where did it start and where will it end. I know not the latter, but I conjecture that it commenced with those in Hollywood and the media, and other places where they created this “aura” of drama and negativity as to the good lives of Italian and Italian Americans. And yes, they claimed it was “art” but it ruined us. The challenge then is how do we recover and get more balance for some of the past was a reality, but certainly not all of it. My hope is that we regain some of what we enjoyed as youngsters and get back to some semblance of respect, order and honor for and to one another. It shall be a stretch!

Pendulums in popular culture always swing back-and-forth. Pazienza!

When analyzing the 1950’s pros and cons, a big pro was the historically unrivaled progress in prosperity for the middle class which has been in erosion ever since. As a 1952 baby I include from my vantage point that “the 50’s” lasted until 11/22/63. Even though women’s suffrage was in 1920, it still appears to me that with minor changes the world was actually the same from the Mesozoic era to that day. As a small boy who conversed frequently with 2 spinster aunts next door, it was always a matter of unceasing pride with our admiration of the Italian-American entertainers, We would also be remiss not to mention those who graced the top 40 rock hits of those days. Just a couple would be, Frankie Avalon and the Four Seasons, the latter who extolled the more gritty East Coast reality at the same time the Beach Boys peddled the surfer culture out West.

Mark Rotella’s book on Italian Americans in popular culture is a must-read on this subject.

I consider our Italian heritage a treasure. It is a free country, if you want to assimilate that is your right. I think you’re making a big mistake. Our secular culture is a dead end, and the evidence is all around us.

Those who ignore the mistakes of the past are bound to repeat it.

For sure! Thanks.

You can add to the “mobster and lowlife” film list Spike of Bensonhurst, Do the Right Thing, The Pope of Greenwich Village, Donny Darko, Coney Island, and Hard to Kill, among others.

The Italic Institute of America’s “Film Research Project” is the best source for this.

Hit the “LIBRARY” menu button, then go to “Film Research Project.” Spread the word!

This blog is a timely reminder, as I try to ponder why on, or around Thanksgiving, of all days, there was a Godfather binge, showing all three films. Why would this be considered entertainment during the holidays?……. and then I am at a total loss to comprehend the mass shootings that are occurring, to the point people are becoming so desensitized that I can’t handle hearing one more comment about memorializing the victims in our hearts….as a knee-jerk response.

I know there is no direct correlation between the current violence and the entertainment media’s obsession with film violence, but the sickos who are into all the media violence have lost any sense of fantasy and reality. The Godfather series among others helped to blur those lines between fact and fiction both in terms of violence as entertainment and the portrayal of Italian Americans. And in many ways, this says more about our society in general, but Italian Americans have more than paid the price for this weird voyeurism.

I actually do see a correlation. We’ve let Hollywood off the hook for far too long. The industry is obsessed with violence. The make very few films about actual human beings.

The results are obvious a) desensitization and b) lack of imagination.

They need to be called out on it. And do so the sheep-like audiences who willingly support Hollywood’s assault on both art and even decently made entertainments.

I can’t help but think the downgrading of us and our culture is purposeful.

And the mobster image being used politically to keep Italian American candidates on the sidelines.

So much of our positive history in all fields is either downplayed or ignored.

Even rewriting history pertaining to Columbus, pertaining to the bravery of the Italian Army during WWII, and on and on.

I also believe there’s a lot of envy in relation to our accomplishments.

Or am I being paranoid?