After decades of Hollywood movies depicting Native Americans as red savages, along came Dances with Wolves, a cinematic game-changer. Whatever its faults — New Yorker film critic Pauline Kael mocked actor-director Kevin Costner with the mock-Indian name ‘Plays With A Camera’ — this 1990 Oscar-winning epic forever altered the way in which Native Americans and their culture were portrayed on the silver screen. Whether in comedies (1998’s Smoke Signals), animations (1995’s Pocahontas) or serious dramas (2015’s Songs My Brother Taught Me and 2017’s Wild River), the first immigrants to America (they trekked over an icy land bridge) are now treated sympathetically — with respect, not mockery.

love the diversity of humanity.”

-Native American activist Leonard Peltier

Even the occasional media embarrassment — such as the revelation that the late Sacheen Littlefeather, who accepted Marlon Brando’s award for The Godfather to chide Hollywood for dissing Native Americans, was herself a fraud (she was Hispanic and European) — hasn’t dented their dignity.

(Sidenote: Yes, the irony is not lost on me that neither Ms. Littlefeather nor Marlon Brando recognized the demonization of Italian Americans via The Godfather. That film was a game-changer, too, though not in the positive way that Dances with Wolves was for Native Americans. And, of course, our nation’s better-late-than-never appreciation for our Native American brothers and sisters has come at the expense of Christopher Columbus, whose journals actually reveal the musings of a man who wanted to Christianize the natives, not stomp them out.)

Italian American filmmakers have become major players in Hollywood’s healthy revisionism concerning Native American culture. (And not just filmmakers, btw: Scholar Camille Paglia’s next tome is dedicated to Native American tribes of the East Coast.)

Shortly after Dances with Wolves, we got Thunderheart (1992), loosely based on the 1973 Wounded Knee incident. It was written by John Fusco, who also wrote the 2002 animated film, Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron and 2003’s Dreamkeeper. Note to Italian Americans in the arts: Despite his love for Native American culture, Fusco also found time to write the Netflix series, Marco Polo, riding horses on the plains of Mongolia as pre-inspiration.

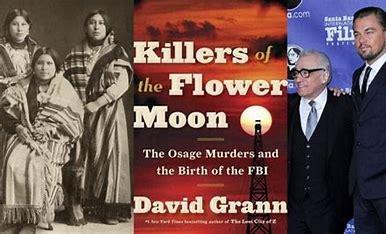

A new 2023 documentary, Lakota Nation vs. the United States, chronicles efforts by that native tribe to reclaim the Black Hills of South Dakota. It is co-directed by Laura Tomaselli and executive produced by actor/activist Mark Ruffalo. And later this year, Martin Scorsese’s much-anticipated Killers of the Flower Moon finally hits theaters, an adaptation of a 2016 book chronicling the murder of Native Americans in 1920s Oklahoma by vicious robber barons.

It is well and good that Italian Americans lend their clout and access to document the Native American experience. Yet you also can’t help but wonder: Why, oh why don’t they recognize that their own community, Italian Americans, needs an equally strong dose of cinematic dignità as well?

Imagine a Scorsese version of the Sacco and Vanzetti case, also from the 1920s. What a way to balance the 50th anniversary of his Mean Streets, with Harvey Keitel and Robert De Niro yukking it up as petty greaseball hoodlums — a far cry from Bartolomeo Vanzetti’s “I have suffered because I am Italian.”

Imagine Mark Ruffalo combining his social justice skills with his alleged Italian pride. Quick example: Why can’t he star in a biopic of Florentine-born Carlo Gentile (1835-1893), who photographed the Pima and Maricopa Indians in Tucson, AZ in 1868 and later adopted a Native American boy? That boy became Carlos Montezuma, an Indigenous activist and the first Native American man to receive a medical degree.

Forty years earlier, Fr. Cataldo founded Gonzaga University in Spokane WA.

Even better: How about Ruffalo doing biopics of Italian priests like Father Joe Cataldo or Father Antonio Ravalli, men whose names are still revered by the Indigenous people in the respective states where they ministered (Washington and Montana)? How about Father Samuel Mazzuchelli, the 19th century priest who ministered in Ruffalo’s home state of Wisconsin? Father “Kelly,” as his Irish parishioners called him, was a prelate whose “command of native languages enabled him to publish texts for the Winnebago and Menonminee Indians of the region.” Father Mazzuchelli is “also credited with publishing the first book in Wisconsin–a liturgical almanac in the Chippewa language” (source: website of St. Patrick’s Church in Benton, WI, built by Mazzucchelli).

Perhaps Ruffalo can talk actress Marisa Tomei, one of his fellow producers on Lakota Nation, to star as Rose Segale, aka Sister Blandina, the Roman Catholic nun who ministered to the Apache and Comanche, and who even talked Billy the Kid out of committing an act of vengeful violence.

(Incidentally, Sister Blandina is currently being promoted for sainthood. If the Vatican approves, that would make her yet another Italian-born American female saint after Mother Frances Xavier Cabrini).

Finally, Ruffalo, Tomei, Scorsese, et. al might also be cheered to note that in 1961, an Italian American judge, Robert Belloni, ruled in favor of Native American fishing rights in the Pacific Northwest. Yes: an Italian American judge. In 1961. Before The Godfather. Before Goodfellas.

Judge Belloni was both a real godfather and a real goodfella — to Native Americans. Just as Ruffalo, Scorsese, Tomei, et. al are to them in 2023.

To see the sad vacuum which this lack of true Italian American pride creates, look no farther than the De Meo brothers, a filmmaking team on the East Coast who recently “celebrated” the second year of their fictional mob series Gravesend. Though tacky to the core, it stars some fairly well-known actors: Chazz Palminteri (and his daughter — congrats, father of the year!), Leo Rossi, Sofia Milos, and Vincent Pastore. A recent article about it showed cast and crew partying like it was 1899 — that is, the year when crude, anti-Italian stereotypes were first celebrated in the national media (newspapers).

Contrast this with what happened on the set of the 2015 Adam Sandler film The Ridiculous 6: Four Native American actors shut down production after calling out the “degrading stereotypes” of Native Americans. We live for the day when Italian American thespians do something similar via a mob movie.

Until then, we must continue to sit on the sidelines while Italian American actors, writers, directors and producers — not to mention wealthy Italian Americans who could easily fund pro-Italic projects if they opened their checkbooks — dignify the history and culture of others.

The dark, nightmarish, anti-American images of The Godfather will continue to define us. Our dreamcatchers have holes in them! -BDC

In many ways, for whatever historical reasons ” a la Jesse James and the whiskey rebellion” I have always contended that the Godfather genre, says more about American pop/folk culture than it says about Italian Americans.

…what is frustrating, however, is how many generational “assimilated Italian Americans jump on the bandwagon since they know so little about their own history…..and more is the tragedy and frustration, in trying to explore this fascinating history..It is a hard nut to crack as your article notes.

Maybe we should reverse the paradigm….and have some Italian American producers deal with mainstream stereotypes…would be fascinating, but I also find it interesting that legislators are trying to curb what people can teach about American history in schools these days so as not to offend mainstream American sensibilities….yet Italian Americans are still “open season”. A little more equality in this area would be appreciated……

The 1999 HBO movie Vendetta did portray the early Italian immigrants in a sympathetic and positive way. More typically, however, we get obscenities like the 1995 movie Two Bits. There is plenty of talent in the IA community and there are plenty of good stories to tell. Unfortunately, however, we are impoverished in the courage and leadership qualities required to bring about meaningful change.

There are many other constraints dragging upon the historical depiction of Italian Americans as a result of the narrow view of the Jewish owned and scripted studio system. Case in point is the Paddy Chayefsky penned Marty, while entertaining and innocuous depictions of 50’s life, is in many ways lacking elements of the true ethnic experience. Italian Robert Alda portrayed Gershwin in a sweeping narrative of of the Jewish American immigrant experience in 1945’s Rhapsody in Blue. Even the Norwegians got a sterling depiction with I Remember Mama. So many or our exceptional mothers’ stories never made it to the screen.

I am happy for Native Americans, at last they are getting some justice. This is my 44th year as a volunteer in the Italian American community and I still don’t see justice for our community. The worst part is the role some Italian Americans have and are doing to hurt our image. There are many examples. One in particular is why can’t we keep Columbus Day and statue across the country? We are a large group, and our cause can be backed up by facts.

I would like to remember the book Rebel Genius by Italian-American Michael Dante Di Martino. In the interview below, Di Martino seems to truly appreciate Italian culture and art on which the above-mentioned book is based.

Unfortunately, there has not been a TV series following the book (2016). This is quite surprising considering the massive success of Di Martino’s previous Asian-inspired tv series Avatar.

I am pretty sure that, if Rebel Genius was not about Italy or if it was about Italian fictional organized crime, it would have been televised.

https://mashable.com/article/michael-dante-dimartino

I Remember Mamma (Nordic people); Roots (African Americans); Schindler’s List (Jews); America, America (Greeks); The Joy Luck Club (Asians); and so on.

What do they share in common? POSITIVE views of an entire people–their struggles and triumphs. We get The Godfather saga–nine hours of Italians behaving badly.

“Impoverished in courage and leadership qualities” sums it up perfectly.

And not just movies. PBS ran a special on the building of the Golden Gate Bridge in the mid-1930s, an engineering marvel. The granddaughter of an Asian American engineer highlighted both her grandfather and the fact that Asians were discriminated against via the 1884 Chinese Exclusion Acts. The main architect of the bridge, Johann Strauss (German Jew), is featured at length. Yet not a single word on who financed the building of the bridge: the banking genius A.P. Giannini (Italian).

Correct me if I’m wrong but would the bridge have been built without any funding?

That the average American doesn’t know the name “Giannini” is a major crime.

Education, education, education. For me, surviving the shamrock SW side of Chi Town, it was self-education thanks to a book, The Italians in America by Michael Musmanno, which I discovered tucked away in our branch library when I was in 8th grade. That started me on a quest to fill in the gaping holes in our history textbooks between Caesar and Columbus and Capone! Did my people simply go dormant for 1400 years then 500 years?

Since the only languages the Irish nuns offered in their high school were Spanish, French and Latin, I chose MY heritage and the ancestral language in which I still pray every Sunday no matter papal or FBI disapproval.

Educate yourselves! Do not wait for one of my fellow actors or writers to do it for you on film. The homeschool movement has been growing since all American parents got a chance to see what really went on in the classroom during the remote Google classes of lockdown. But even if you must keep your child in a religious or government school during the day, that does not absolve you from homeschooling them and yourselves on our language, history and arts.

By the way, when I teach in our local “public” school, I will introduce the etymology of a word with Latin roots by saying: “My Roman ancestors’ word was __________ from which we derive this English word.” When teaching geography and history, I will say something like: “And helping the Frenchman LaSalle explore our region was the Italian explorer Enrico Tonti.” My point is there are a million ways in which you can pass along curiosity and pride in our Italianita!

REPLY to Beverly Coscarelli

There sure are a million ways. I’ve done similar such things during my 25 years as a high school teacher, e.g., highlighting Filippo Mazzei during a unit on the American Revolution or noting the names of Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Gregory Corso and Diane DiPrima via a literary unit on the Beat Poets. But I don’t have Scorsese’s “millions.”

Self-education is something which our millionaire actors, writers, directors, and wealthy people have NOT done. Are they obligated to do so? Not in a free society.

But they certainly take the time to educate themselves on other Americans’ history and culture, pouring their talent–and their millions–into dignifying such stories.

“Don’t kill the actor!” This misses the point. Our cultural leaders–through their ignorance and lack of funding–are killing ITALIAN AMERICAN culture. It is dying.

I recently became aware of a newly released movie, The Hill. It appears to be a very inspirational movie directed by Jeff Celentano, with a screenplay by Angelo Pizzo (of Hoosier fame). Angelo Pizzo also wrote the screenplay for the movie: The Game of Their Lives about the very first US soccer team, which beat the vaunted English team in the World Cup. Quite a few of the members of that US team were Italian Americans from “The Hill” in St. Louis. If we could unleash the talents of Italian Americans like Celentano and Pizzo in creating positive IA movies, it might set a long-awaited new trend.

In an interview many years ago, I recall Martin Scorsese stating that he wished he could produce a film as significant as IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE which we have all seen at Christmas. Well, there can be. It is the biography of Ferdinand Pecora. He came to America with his family as a young boy. He overcame prejudice from being Italian and his religion. He stopped his law studies and put his duty to family first after his father died. He eventually became the DA in NYC and later was appointed by Roosevelt (who said it was ok since he is Italian, so nothing will get done) to head the congressional investigation on why the depression occurred. There was limited time left in the investigation since previous investigators failed. The hearings were so popular that there was standing room only and the hearings were broadcast nationally. Because of his investigation congress enacted the Glass–Steagall Act, among others. At the onset of the war, he tried to enlist but was rejected due to health. He dedicated his life to duty, family, and country (sound familiar?). Leave out the infidelity and you have the making of It’s A Wonderful Life, Italian style! A film of a real person that would give Italians pride. Martin, I hope you are listening, (read The Hellhound of Wall Street by MA Perino).