Celebrating New Year’s Day on January 1st is definitely a Roman development. Like so many other facets of our existence, Italy figured large in mastering time.

We learned in school that the Egyptians, Babylonians, and Sumerians all studied the heavens and developed the sun dial, the water clock, and the 60-second minute and 60-minute hour. Moreover, agricultural societies required divisions of the year into predictable seasons. So, the ancient Persians devised an accurate solar calendar, as did the Mayans and Aztecs. But somewhere along the way, the moon replaced the sun as a guide to seasons. The result was chaos in the fields.

Both the Jews and Chinese still love their erratic lunar calendars with a year of 354 days instead of 365¼. Those missing 11 days really screwed things up as the years went by. Today, both ethnic groups confine their lunar calendars to religious and cultural timekeeping. To get along in the modern world, they depend on the Italian (“Gregorian”) calendar.

The most practical of all ancient peoples, our ancestors didn’t just complain about bad calendars they created new ones. In 153 B.C., the Romans moved New Year’s Day from March 15th to January 1st to adjust the seasons without bothering to rename September, October, November, or December – that’s why those prefixes don’t match their calendar positions. In 46 B.C. Julius Caesar had his stargazers perfect the solar year by dividing up the days of each month better – still, the new calendar was off by 11 minutes a year. Fifteen hundred years later those lost 11 minutes wreaked havoc on the celebration of Easter – it was supposed to fall on the Spring Equinox, not mid-winter. So, Pope Gregory XIII (aka Ugo Boncompagni) adopted a new calendar in 1582, devised by a Naples-educated astronomer from Calabria named Luigi Lilio (aka Aloysius Lilius). This is the “Gregorian” calendar the world uses today – but it’s still off by 26 seconds every year!

Keeping time during the day was another task Italians tackled. Sundials had some use during sunny days, and Roman water clocks were subject to leaks and evaporation. The Chinese claim the invention of the first mechanical clock back in the A.D. 900s, but it was a huge water wheel, not the compact springs, gears and sprockets we understand as mechanical. By the early Renaissance real mechanical clocks appeared on some churches in Italy and Germany that had bells to ring out the hours (no clock hands). In Medieval Latin “bell” was clocca, which gave the English a name to call the invention – a clock.

In the late 1500s, Europeans were producing mechanical clocks of varying accuracy. Missionary Matteo Ricci brought some with him to China to gain favor with the emperor. The Chinese caught on quickly, copying the designs and allowing Ricci to preach the Gospel.

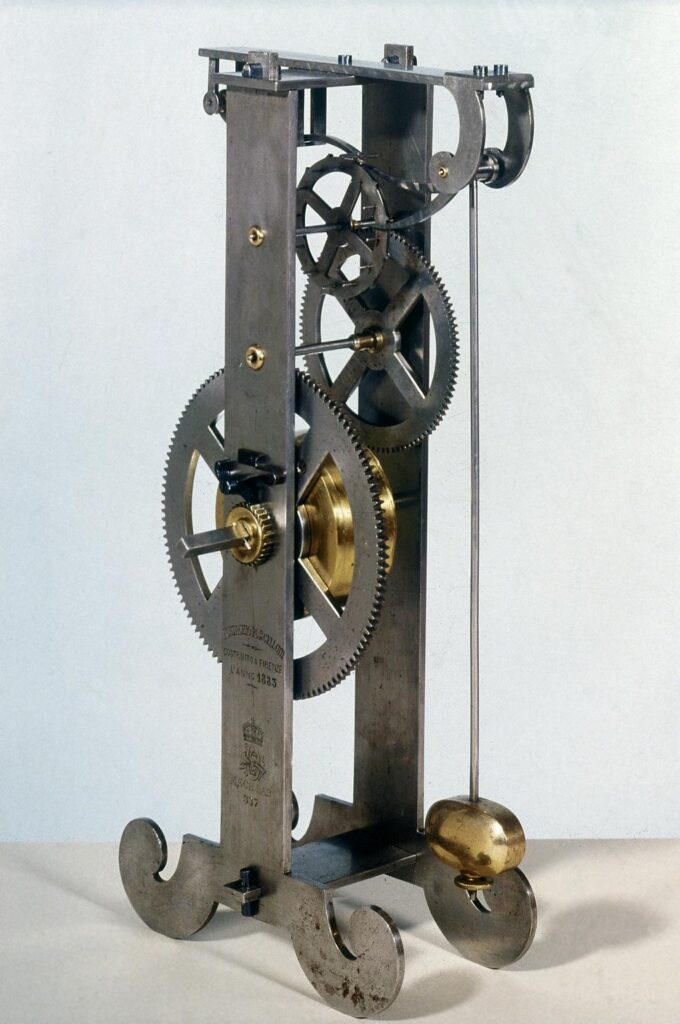

Back home, making clocks more precise led scientist Galileo to consider a pendulum to regulate the speed of the gears. He died before perfecting a pendulum clock but his son Vincenzo designed a prototype. In 1657, Dutch inventor Christiaan Huygens used Galileo’s theory to patent the first real clock (with hands, using a pendulum and weight drive).

Marking time was clearly an Italic pastime. Dating time was another development that Classical Rome passed on to the world. Our dating system is divided by the life of Jesus – BC, Before [the birth of] Christ; Anno Domini, ‘the year of the Lord.’ Church sources credit Dionysius Exiguus, a monk-scholar with this system. He came to Rome around A.D. 496 and convinced the Pope to replace the old pagan dating system with one based on Jesus. Dionysius was not Italic but he remained in Rome the rest of his life. The Catholic Encyclopedia notes that despite his origins, Dionysius was considered by his Italian contemporary Cassiodorus to be “a true Roman and thorough Catholic.”

We are all aware that academic forces are replacing BC and AD with BCE (Before the Common Era) and CE (the Common Era). The Italic Institute will continue using BC and AD. But it wouldn’t be shocking to assume the C in BCE and CE stands for ‘Christian.’ -JLM

Recent Comments