On the occasion of singer Tony Bennett’s 96th birthday (August 3rd), it’s sobering to recall his famous comment after the premiere of 1972’s mobster epic, The Godfather.

To wit: “It’s a terrible, terrible film, just pernicious. Despite its marvelous directorial techniques, it leads viewers to believe that organized crime is all-Italian when, in fact, it consists of many nationalities.”

Forty-one years later (2013), retired New York Governor Mario Cuomo finally watched The Godfather after refusing to do so for decades. His post-viewing comments are eerily similar to Bennett’s:

“Maybe this thing is a masterpiece. But the message it sends is horrible. It says that Italian Americans have no respect for the Rule of Law.”

Both of these gentlemen ̶ a word which, like “law-abiding”, the media also never applies to Italian males ̶ easily saw through Mario Puzo and Francis Ford Coppola’s “Big Lie” ̶ namely, that “Italian culture” and “crime” are synonymous.

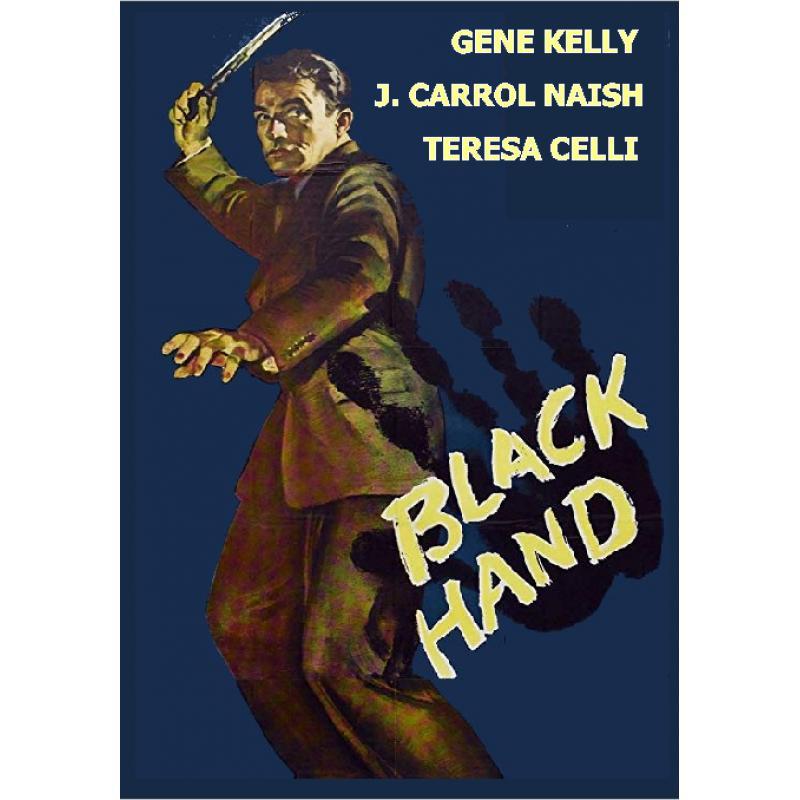

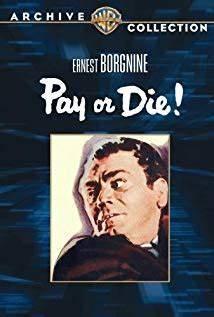

To gain a better perspective on this, it’s instructive to look at how Italian Americans were portrayed in Hollywood films in the pre-Godfather era. And it’s even more instructive to do so by comparing two films made about The Black Hand (La Mano Nera), the Italian criminal gangs who preyed upon fellow immigrants in poor neighborhoods: The Black Hand (1950), with Gene Kelly, and Pay or Die (1960), with Ernest Borgnine as NY cop Joe Petrosino.

In each of these movies, as in even earlier films like Little Caesar (1931) and Scarface (1932), the roles are reversed, and rightly so, given the reality: Italian Americans are the victims, not the predators. People involved in illegal activities, including murder, are seen as a blight on the Italian American community, most of all by fellow Italians.

(Or, as Borgnine’s character, the heroic Petrosino, says, referring to these criminals, as “scum” (schifosi).

Cut to The Godfather. According to writers like Maria Laurino, it was the film’s “genius” (!) to view the murderous Corleone gang through a warm, sympathetic lens ̶ in short, as a typical Italian family. Anyone and anything Italian in that film was “connected” to illegal activities. Even the women characters, who in The Black Hand and Pay or Die were outspoken moral compasses in those films, urging fellow Italians to fight the mobsters, kept their mouths shut.

In an October 2003 interview in Cigar Aficionado Magazine, Coppola himself admitted to this egregious blurring of fantasy and reality: “I had no experience or knowledge of the mafia. In the end, they were just an Italian American family. I based the film on all of my uncles and my relatives. They were musicians and little businessmen and tool-and-dye makers…In acting, they call this substitution.”

In real-life, they call this propaganda at best, prejudice at worst. And, in his 1969 potboiler, Puzo combined both.

There’s nothing romantic about la mano nera thugs in the pre-Godfather films. In The Black Hand, a respected Italian lawyer is harassed and murdered by them, which leads his young son (Kelly) on a life-long journey to avenge his father. In Pay or Die, Borgnine/Petrosino, after literally tossing a gangster into a garbage can (yes, symbolic), turns to the astonished residents and screams, “There is no mafia. There are just gangs.”

(Technically correct: the “Mafia” is terrorist criminal gang in Palermo, Sicily. What we had/have in the States is organized crime, which, to quote Bennett again, “consists of many nationalities.” Also correct. But you wouldn’t know it because the media focuses solely on Italian surnamed criminals. Even the now-disgraced former mayor of New York, Rudy Giuliani, publicly complained about this unfairness once; he noted that the media highlighted Italian gangs more than the “20 or so organized crime groups my office regularly prosecutes.” In crime, “diversity” becomes a bad thing.)

From an artistic standpoint, I found Black Hand, the earlier film, more professionally done than Pay or Die. Its director, Richard Thorpe, has a better grasp of film technique; he moves the camera, shows an eye for black-and-white lighting contrasts, and employs a few flashier effects (e.g. a montage showing extorted monies being paid to Italian crooks, and the screen going blurry when Kelly is hit on the head from behind). This film, too, features Joe Petrosino, in this case, a detective named “Lorelli” played (very well) by the legendary character actor J. Carroll Naish. Petrosino’s death scene ̶ he was murdered in Palermo by thugs in 1909 while conducting a private investigation, though this film sets it in Naples ̶ is better-staged than the one in Pay or Die. It is film noir at its best ̶ no music, just dark shadows.

Pay or Die does have its virtues, although the cheap look of the film (very low budget) and the pedestrian pacing often flag your interest. The opening act of violence, set during an Italian religious festival, still packs a literal wallop. The characters speak about seeing Enrico Caruso in concert, a reminder of when Italian culture once did unite Italian Americans until we went our assimilated ways. And one of Petrosino’s young protégés (he inspired many Italians to become cops) speaks a line totally in spirit with the aforementioned ones by Bennett and Cuomo: After arresting and almost beating a mano nera criminal, the young officer stops and says, “Every fiber of my being says I should kill you, but I remember what he (Petrosino) taught me: We live by the law.”

If Don Vito Corleone repeated that statement at a family dinner, everyone would raise their glasses and laugh, cynically. Today’s Italian Americans, however, raise a glass and salute the Corleones for, indeed, undermining American values.

Hollywood’s “black hands” continue to leave their dark imprint on Italy, Italian Americans, and Italian culture.

(Note: The author wishes to thank Bob Masullo, a retired reporter for the Sacramento Bee newspaper in California, for suggesting a comparison of The Black Hand and Pay or Die.

Nota bene: In 2017, actor Leonardo DiCaprio announced a new film version of the Joe Petrosino story; however, the project appears to be in limbo. DiCaprio has since moved on to a biopic of Leonardo Da Vinci, based on Walter Issacson’s recent book, and an upcoming project with Martin Scorsese, Killers of the Flower Moon.

The Da Vinci pic seems to have been motivated by the chapter in Issacson’s book on the artist’s rumored homosexuality, and the Scorsese pic is about the true-life murders of Native Americans in 1920s Oklahoma.

Bottom line: Italian Americans still have yet to crack the media’s “PC” or “Woke” barriers. We remain predators. -BDC

The extent of the negative stereotyping of Italians and Italian-Americans is not fully known and understood in Italy. It is rare to read about it on Italian media. I learned about it only after moving to the US and experiencing it first hand.

Federico Rampini (Corriere della Sera) is a famous Italian journalist who has been living in the U.S for decades. I usually read his articles and I was surprised to finally see a brief reference to the problem in one of his recent articles. I attached the link below.

He suggests that the stereotyping exists but it is limited to the “less sophisticated” Mid-America. He only mentions The Godfather and The Sopranos. I suspect many Italians in Italy think that the stereotyping is limited to only those major movies or TV shows. They do not know there are actually hundreds of movies and TV shows systematically portraying a negative image of Italians and Italian-Americans. Also, many Italians believe that the stereotyping applies only to Southerners from Naples, Sicily or Calabria. They may naively assume that the problem does not apply to an Italian, let us say, from Milan.

https://www.corriere.it/cronache/22_luglio_14/negli-stati-uniti-ci-amano-ma-oltre-cibo-arte-sopravvive-ancora-stereotipo-padrino-7afcb0a2-02f8-11ed-a0cc-ad3c68cacbae.shtml

Signor Rampini apparently isn’t familiar with our (the IIA’s) 2015 Film Research Study, available on our website: https://www.italic.org (click on Research Library).

The stereotyping is overwhelming, both statistically and even anecdotally. And the people who stereotype Italians the most? The “sophisticated” types in L.A. and NY.

He’s also deeply kidding himself if he thinks the average American distinguishes between southern Italians and Yuppie-types from Milan. In the media’s eyes, ALL Italians are suspect. The stereotyping is complete and total. In fact, I once overheard a middle-aged American couple, traveling in Milan, make a joke about a local restaurant being owned by “the mafia” because the food wasn’t very good.

You want to see anti-Italian-American stereotyping? Check out the films Spike of Bensonhurst and the Steven Seagal flick Out For Justice. Also, the depictions of Italian-Americans in the Brooklyn Three crime trilogy by the late Brooklyn College professor Thomas Boyle is a good example of open hostility towards this ethnic group, e.g. depicting yuppies being afraid to move into an Italian-American neighborhood due to the high crime there. That neighborhood, btw, is called Carroll Gardens and is real, and was one of the safest areas in NYC. I should know, since I grew up there. That’s why it became gentrified.

Clyde Haberman of the NY Times said the following about Spike Lee back in 1999:

“If a white filmmaker portrayed Blacks the way Lee portrays Italians in his movies,

he would be denounced as a racist and run out of Hollywood.” Indeed.

This has been a serious problem for our community for a long time.

Thank you all for correct remarks and being part of the solution rather than the problem!

I try my best. “Knowledge is power.”

How is Rudy Giuliani disgraced?

Because, in the new Peoples’Democratic Republic of the USA, to question whether 81 million votes equals 81 million legal, living American citizen voters voting only once labels you as a loon OR a wise and cynical life-long Chicagoan such as I.

I refer you to John Mancini’s last blog about “America’s Mayor.” From his public cross-dressing to his gleeful embrace of mob stereotypes (despite putting them in jail!), he has not done our heritage proud. His current “stop the steal” campaign also hurts.