Will popular history ever reveal how crucial Italians were to opening the New World? There is so much already known of this “Italian enterprise” but buried in a few books. Sadly, our community is consumed by the struggle to save the reputation of Columbus from revisionists and the ignorant woke – one Italian among the many who unified the globe.

another target for Indigenous people

So many myths, so little time. There’s the one about Queen Isabel hocking her jewels to finance the Admiral’s first voyage. Happily, it was the Italic Institute that “discovered” a little known book by South American historian Germán Arciniegas (Amerigo and the New World, Knopf 1955) that detailed how Isabel required Columbus to raise most of the money from Italian bankers and merchants in Spain – Italians not Jews dominated the financial world of the Middle Ages. Isabel, in turn, borrowed her share from an Italian and a Jew. The real back story.

Now come new revelations about Giovanni Caboto whose voyages to the New World five years after Columbus gave England claim to the east coast of North America. The late English historian Alwyn Amy Ruddock became the expert on Italian financing of discovery starting with her 300-page volume for the Southampton Records Series I, Italian Merchants and Shipping in Southampton, 1270-1600. Just before her death in 2006 Ruddock had come upon some amazing revelations about the Italian role in English exploration. She never finished her book and willed that all her research and notes be destroyed. Much was lost except for a Post It with the handwritten words “The Bardi firm in London.” This tidbit led other researchers to contact a historian in Italy who found a ledger in Florence showing the Bardi firm contributing to Cabot’s voyages from Bristol, England between 1497-1500. Like Columbus, Cabot was financed by his paesani.

Ruddock previously discovered what prompted Cabot’s voyages – Italian piracy. Forty years before Columbus’s discovery, an English entrepreneur named Robert Sturmy of Bristol tried to break the Italian monopoly in the Mediterranean. Genoa and Venice pretty much ruled the Med, buying Asian products from the Arabs and selling them dearly to the rest of Europe. They sold not only spices but alum, a mineral used in dyeing fabrics – the English used tons of it for manufacturing textiles. In 1457, Sturmy convinced the merchants of England to bypass the Italians and get the alum directly from the eastern Mediterranean. Unfortunately, the Italian merchants in Bristol found out about Sturmy’s plan and sent word to Genoa.

Sturmy’s fleet sailed undisturbed into the Med and loaded up on alum as well as other rare products. That’s when the Genoese pounced. They ambushed the English and seized the cargo, killing Sturmy in the process. When word reached Bristol the English took revenge. They arrested all the Genoese in England and seized their assets. The Sturmy disaster had cost the English some $1 billion. It killed their Mediterranean ambitions for centuries.

In 1492, the Genoese Columbus opened the Atlantic route to “Asia.” But the English wanted no part of any Genoese navigator and opted for a Venetian – Giovanni Caboto. Cabot had non-Genoese Italian backers in Bristol including the Pope’s representative, Fra Giovanni Antonio Carbonaro. He was a deputy collector of Papal taxes in England—this was before the Reformation! Fra Carbonaro not only hooked Cabot up with Henry VII but he went along on one of Cabot’s three voyages.

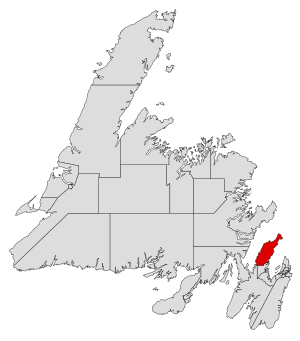

Researchers found that the late Ruddock had evidence of Fra Carbonaro landing in Newfoundland with Cabot in 1498. He supposedly built a settlement that included a church in Conception Bay, which would have been the first in North America – before St. Augustine, FL – at the place now “coincidentally” named Carbonear. Archeologists are already digging for proof.

How many other Italian back stories are buried in archives? – JLM

That is a fascinating behind-the-scene “discovery” regarding the financial houses that supported both Caboto and Columbus. The Age of Discovery in the 1400’s also included multicultural and multi-lingual communities among the ruling empires, especially the newly emerging Spanish empire. Today they are considered nations, such as Italy. My favorite, local connection is that the original name of the mission town of Santa Cruz, California, was founded by the Spanish and the pueblo was named after the Spanish Viceroy Branciforte, whose family origins are from around Trabia, Sicily, which at that time was part of the Spanish Empire. There are still a couple of streets named after him in Santa Cruz. Thankfully no one knows or cares about the origin of the name, or someone would probably want to rename the street!!!!! (Incidentally, there are more people from Trabia in San Jose, California than in Trabia, Sicily today).

What amazes me that the information is available about what Italians and Italian Americans have contributed. Recently I read about the inventions of Italians and how they have changed the world from the radio to the telephone and much more. For most people the reaction is so what? Many do not have the information and many more could care less. We live in age when many people don’t read, have very limited interest, and many are brainwashed. I don’t think we should give up, but in order to solve a problem we need to know what the problem is. Today we have so many sources for information, we need to find ways to get more people to want the information.

Another “back” story is the one about Amerigo Vespucci and the name “America”.

My impression is that the vast majority of Americans do not know where the name America comes from.

I have a child and the Amerigo Vespucci story is not taught in elementary school for sure (yet it is pretty “cool” and intuitive for children — Amerigo, America). However, my child has already been exposed to well known lies about Colombo. I am sure if Amerigo had been Anglo Saxon/Scandinavian/Jewish/African, the story will be part of any curriculum.