Last week, a “tall ship” visited my Long Island village, a port of call that has seen the HMS Bounty and replicas of every kind from the Age of Sail. This time it was the Nao Trinidad, one of Ferdinand Magellan’s Spanish galleons that first circumnavigated the globe in 1522.

Magellan was Portuguese who, like Columbus, couldn’t convince the king of Portugal to sponsor his quest but found a willing partner in the Spanish monarch. The quest: Columbus had proved that sailing west to reach the East Indies wasn’t a crazy idea. In 1503, Vespucci surmised that a New World was blocking the way, but no one knew if there was a way around it. One Spanish captain had gone as far south as Argentina in 1516 but was killed by not-so-peaceful indigenous people. Magellan wanted to pursue that southern course when his fleet of five ships left Spain in 1519.

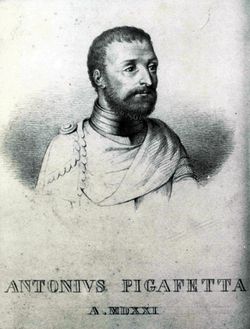

Circumnavigating the globe was not to be just a commercial venture for Magellan but a scientific one. To observe and record the feat he brought along Venetian scholar Antonio Pigafetta and some 26 Italian crewmembers. Of the 240 men who set out from Spain on the 3-year voyage, only 18 completed the trip – Pigafetta was one of them; Magellan was killed in the Philippines by the locals and Pigafetta was wounded in the same ambush. It was Pigafetta’s journal that documented the circumnavigation and saved Magellan’s reputation. The other survivors and the Spanish ship captains who had deserted Magellan’s fleet before it reached the Pacific Ocean all denounced their deceased captain for being Portuguese and for personal reasons. Only the Italian stayed loyal to the late navigator and glorified his deeds.

Magellan had found the way around South America, now named the Strait of Magellan, he also brought Christianity to the Philippines and gave Spain a Pacific empire. He proved that the globe was linked by oceans and expanded the spice trade. Pigafetta’s observations gave geographers a more accurate circumference of the Earth and the locations of new Pacific islands like Guam.

One of his lesser-known revelations concerned Earth’s time zones. From the first day they left Spain, Pigafetta noted each day of the week. Near journey’s end, when his ship reached the Atlantic Ocean in 1522 and landed on the Portuguese island of Cape Verde off the coast of West Africa, Pigafetta assumed it was Wednesday.

“[But]… to the Portuguese it was Thursday…and we knew not how we had fallen into error. For every day I, being always in health, had written down each day without any intermission.”

Somewhere along the journey a whole day had apparently been lost. Pigafetta tried to make sense of it:

“We had always made our voyage westward and had returned to the same place of departure as the sun, wherefore the long voyage had brought the gain of twenty-four hours, as is clearly seen.”

In short, the fleet had crossed 24 time zones and what we now call the International Date Line, something first conceived in 1876 – 354 years after Pigafetta.

Antonio Pigafetta is acknowledged on the replica Nao Trinidad in a mural displaying Magellan’s voyage. There is even a statue of him in the Philippines and in his home city of Vicenza, Italy where he died and is buried.

In my last blog I noted that June 24th is fixed in history as the day in 1497 that Giovanni Caboto claimed North America for England. To my surprise, the almanac for that day as published by the Associated Press and distributed to subscribing newspapers around the country, had this anemic entry: “The first recorded sighting of North America by a European took place as explorer John Cabot spotted land…” No mention of planting the English flag or that the event led to the British Empire and to an English-speaking continent. No less than Benjamin Franklin memorialized Cabot’s June 24th landing in a 1775 essay defending the rights of the thirteen colonies. Beware of the AP’s disinformation!

Whether it be a Caboto or Pigafetta, behind every historic event you may find an Italian. -JLM

These certainly are amazing pieces of insight, well beyond History 101. We like our history clean and simple, which it really is not… it is like life, messy and complicated. I had an accelerated course about the Italian navigators of the Renaissance and technology when I tried to engage in dialogue about Columbus and his navigational skills…to not much avail since the motivation was not actual fact-finding but propaganda, of which truth is an irritant.

And speaking of the Renaissance, I had to dust off one of the classic tones of the epoch to understand what’s going on in Russia today….Putin needs to re-read Nicolo Machiavelli’s The Prince and the Discourses…not sure how it will play out in Russia, but mercenaries are a dangerous game, as the Italian Renaissance experienced firsthand.

Can you imagine an Italian American charter school that would elevate those who “identify” as Italic in real Italian history and our immense contributions to humanity. Of course it could only be condemned as a form of “White supremacy.” So, we must be content with “owning” the mafia and the kitchen.

but this observation hits at the heart of the matter, of why we can not engage our youth to support Italian Americana…I go to many multicultural events….and see a lot of youth participation. Italian American events see middle age and above, and part of this is that Italian-Americans have never had any visibility in the school curriculum, save for Columbus et. al. We “discovered it”, and named it and disappeared…. even to the point of not being considered Latin!!!!!!!

I once tried to develop a course on Italian American literature, at a local community college, and the course was rejected, as not engaging enough and would not draw students. Our education system has truly failed to educate its society about what multiculturalism really is….a tapestry of diverse fibers..and not a politically correct patch job. The challenge is to start building upon the very few school systems in the nation that have some semblance of awareness of Italian American Heritage and language skills.

there is a lot of material out there, but it never reaches our educational system, so Italian American Youth are just not exposed to this component of our heritage within the concept of academia..