Among Italy’s national holidays is Liberation Day on April 25th. It commemorates the day in 1945 that a coalition of Italian partisan groups in northern Italy put the last nail in the coffin of Fascism and the German occupation. Four days later the German Army in Italy surrendered to the Allies and Mussolini was summarily executed by Communist partisans. (Elsewhere on that day the Soviets had surrounded Hitler’s bunker in Berlin.)

on a Soviet stamp

Liberation Day is not without controversy. While the notion of Italians freeing themselves from a brutal German occupation appeals to the national conscience, the reality is quite different. Partisans did not free Italy, the Allied armies did. From the invasion of Sicily in July, 1943 to May, 1945 some 60,000 Allied soldiers were killed as they fought their way up the Italian peninsula. They fought not only the Germans but Italian troops still loyal to Mussolini, who from mid-1943 to May, 1945 headed a German vassal state in northern Italy called the Salò Republic.

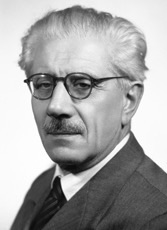

Many courageous partisan groups sabotaged the German occupation from within, but the bulk of their efforts were directed against fellow Italians defending the Salò Republic, essentially a civil war. An estimated 35,000 partisans and 35,000 Fascist troops were killed in this civil war. In addition, according to Italian Communist leader Palmiro Togliatti in a later communication with Joseph Stalin, 50,000 Fascist officials and their families were murdered in a post-war reign of terror. This was all part of a plan for a Communist takeover of post-war Italy. It was Togliatti who for the same reason ordered Mussolini’s execution despite orders from the Allies to turn him over for a trial.

As part of the 1943 surrender terms, this was one of the conditions demanded of the anti-Fascist Italian government:

“Benito Mussolini, his Chief Fascist associates and all persons suspected of having committed war crimes…will forthwith be apprehended and surrendered into the hands of the United Nations.”

Clearly, Togliatti and his partisans had no intention of abiding by the Anglo-American terms. They reported to a higher authority – the USSR. As one OSS (forerunner of the CIA) agent put it: the partisan groups were divided as “…20% for Liberation and 80% for Russia.”

Italy’s first anti-Fascist prime minister Ferruccio Parri (June, 1945 – December, 1945), and himself a partisan, had this to say of his fellow partisans:

“In the partisan movement there were the good and the bad, the heroes and the looters, the generous and the cruel. There was a people with its virtues and its vices. There were the partisans of the eleventh hour, in general a detestable race. And then the exploiters and profiteers of the partisan movement.”

Liberation Day covers a multitude of sins, and many nostalgic Italians now use the day to honor those who fought and died for the Salò Republic, just as different parts of our own country honor the Blue or the Gray on commemorative days.

By design, Liberation Day replaced the previous Fascist “Birth of Rome” holiday which fell on April 21st. The city of Rome has been celebrating its legendary founding by Romulus on that date in 753 B.C. since Roman times. The Fascists made it a national holiday to re-Romanize Italy. To placate the other nineteen Italian regions, Mussolini hijacked May Day (May 1st – the traditional socialist Labor Day) and joined it with the April 21st holiday. This way all the Italian regions had an excuse to celebrate on the same day.

It may be none of my business, but I cannot justify Liberation Day as a pivotal day in Italian history. By April 25, 1945, the partisan “uprising” was more glitz than blitz. It marked the start of a Communist purge rather than an expulsion of the Nazis, which was the work of the Allies. At least the Birth of Rome eventually gave us a unified Italy and Western Civilization. Those are reasons to celebrate. -JLM

I absolutely love learning the history of Italia. Keep up the great work!