Currently, the movie Cabrini is being shown in only one theater on all of Long Island. The same scarcity is probably true in regions around the country. Cabrini is a $50 million production starring Italian actors and many well-known Americans like John Lithgow. All aspects of the production and locales are Hollywood quality, yet the subject matter limits its distribution. I viewed it at a matinee with only six people in the audience.

Nevertheless, Cabrini is a must-see for anyone with a speck of pride in the Italian heritage. Your reaction to the treatment of early Italian immigrants will be an emotional one. Mother Cabrini’s indomitable struggles to improve their lives will be inspirational. Her story borders on the unbelievable, but this is not a fictional movie. I will go so far as to recommend Cabrini as a class trip for high school students of Italian and as an activity for social organizations. Perhaps filling theater seats this way will prolong and even expand the showings.

At 2-1/2 hours long, and much of the dialogue in Italian (with subtitles), Cabrini covers a lot of ground. Still, it doesn’t present the whole story of Mother Cabrini’s accomplishments.

Born in 1850, the youngest of 13 children of farmers in Northern Italy, Cabrini had a heart condition which should have either killed her early on or sidelined her from rural life. She chose to become a teacher and a nun, eventually planning missionary work in China. But when she sought to go to China, Pope Leo XIII redirected her to New York where thousands of poor Italian immigrants were settling in the most squalid conditions.

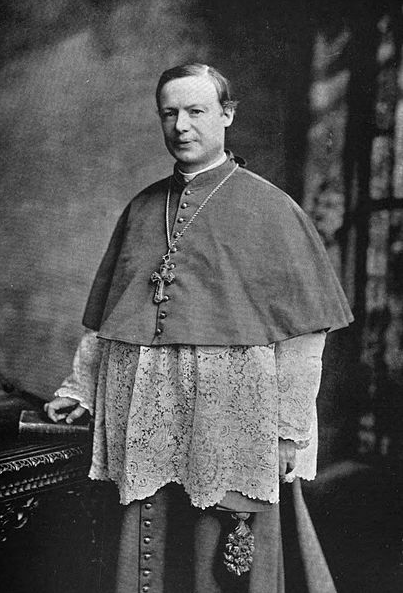

Mother Cabrini arrived in New York with six companion nuns in 1889. The Irish American archbishop at the time was Michael Corrigan who had little sympathy for the “not very clean” Italian immigrants. He relegated them to church basements for Mass and forbade them from building their own churches and care centers lest they siphon money from American donors. What the movie doesn’t convey is the back story of Corrigan’s reluctance to help Cabrini – a resentment toward another Italian who was prominent among New York City’s elite.

Count Luigi Palma di Cesnola was a Medal of Honor winner from the Civil War who founded the famous Metropolitan Museum of Art. Di Cesnola wanted Mother Cabrini to operate a planned orphanage for Italian children near St Patrick’s Cathedral. Archbishop Corrigan didn’t want Italians anywhere north of the Lower East Side. Keeping Cabrini and her staff from DiCesnola’s employ was his goal. But as the movie shows, Cabrini found her own way to finance an orphanage and hospital.

She decided to return to Italy for financial aid. But the Vatican turned her down, leaving her only the Italian government as an option. At the time, the Church and the Italian government had an adversarial relationship. Nevertheless, Mother Cabrini forced her way into a session of the Italian Senate – a Catholic nun among anti-clerics – demanding that Italy support its impoverished children in America. This scene in the movie is quite vivid, although there is no record of it in the sources. When Cabrini screenwriter Rod Barr was asked about his source he replied that it was legendary in the Order of Cabrini nuns. “I discovered an amazing scene, passed along from nun to nun, that would become essential to the arc of the movie.”

In short, Mother Cabrini shamed Italy into partly funding a hospital for immigrants in New York. Construction began in 1892, and appropriately named Columbus Hospital. In July 1973, Columbus Hospital and Italian Hospital (founded in 1937) merged. By 1976, it was using the name Cabrini Medical Center. In the 1980s, it was one of the earliest hospitals to develop treatments for the AIDS epidemic.

At its end, the movie maps the worldwide accomplishments of Mother Cabrini in serving humanity. Besides hospitals, schools, and orphanages, she inspired others like Mother Teresa. Truly, a saint! -JLM

When this movie first came out, I told my wife it would not do well. In my opinion, the movie is not showing in more theaters is twofold. First it deals with the Catholic Church and second it deals with Italians. If it dealt with another ethnic or religious group, it would have top billing.

I believe you also meant to say that Cabrini is about good Italians, not criminals.

John, I agree with you that this movie is a MUST see for every Italian American. It is a powerful movie which shows the reality of the times regarding Italians in New York and the magnitude that Mother Cabrini had on not only them but the entire world. A thank you to those people who made this movie happen and I’m pretty sure I didn’t see the names Coppola or Scorsese in the credits.

We were fortunate to have a couple of theaters, showing it locally but the film did not last long. My amazement is at the commitment of the producers to fund the film. I am sure there is a back story there too.

Still the film went under the radar, even though many Italian American organizations tried to support it….It was released in our area around International Woman’s Day, to try to piggy back on the theme….still attendance was poor and hopefully it will be out on NetFlix and similar online outlets to get the viewership, and recoup the financial cost of making this first-rate movie. I wonder how it has played out in Italy?

The film is also a good teaching moment and locally I wrote a review, but too long for a blog, A couple of “elephants in the room”, stand out, such as how the church/state split impacted governance in Italy for years to come, and ironically the mass migration out of Italy occurred after unification.

Mother Cabrini in many ways was a true spiritual leader and found a way to move beyond partisanship to do her work…a skill perhaps only a saint possesses, and why we aren’t seeing much of it in today’s world, although sorely needed!

The film has generated negative critiques by Catholics who feel Cabrini wasn’t religious enough (they probably wanted a scene with Cabrini talking to the Virgin Mary or Jesus!). I can see why some Irish may not like their portrayals – but they were quite balanced, more than we ever get in mafia movies. I even heard some Italian diplomats didn’t like the way their government was portrayed.

Ironically, all these critiques are sotto voce meaning the film hasn’t achieved open controversy, something that would spur attendance and debate. Without Catholic support or the gift of controversy, Cabrini will not even get attention on NetFlix or DVD.

I had the pleasure of seeing Cabrini at the Malvern theater on Long Island. Granted I saw it on Wednesday at 7PM and there were only 6 people including me & my wife. It was the best movie I have seen in a very long time. I understand how people could be offended by how the Catholic Church was depicted but the facts are the facts. Italians were only allowed to celebrate mass in the basement of the church that usually had a dirt floor. Let’s see if this movie is nominated for many awards as rightfully it should.