On May 24th, 2021, music fans celebrated when one of America’s greatest singer-songwriters, Bob Dylan (a nice Jewish Midwestern boy, born Robert Zimmerman in Duluth, Minnesota), celebrated his 80th birthday. It seems hard to believe that this iconic musical legend is entering his eighth decade – and, even more incredibly, that he still shows no signs of slowing down.

Last June, during the pandemic, he released his 39th studio album, Rough and Rowdy Ways, which made it to #1 in Great Britain. Dylan became the “oldest artist to ever score a No. 1 of new, original music” (Paul Sexton, June 26, 2020, Billboard).

And in 2016, Dylan became the first songwriter ever to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. In addition to a monetary prize (around $1.3 million in U.S. dollars), winners are given a beautiful gold medal with a Latin inscription from Virgil’s Aeneid, to wit: Inventas vitam juvat excoluisse per artes (“And they who bettered life on Earth by their newly found mastery”). The medal features a young male sitting under a tree, looking up at a muse. How many people are aware that the young (early 1960s) Bob Dylan did, indeed, have his own female muse – an Italian American woman who inspired him during his early artistic development?

The Romans had their classical goddesses. Dante had his beloved, unattainable Beatrice. In modern times, filmmaker Vittorio De Sica had his fellow Neapolitan, actress Sofia Loren. And Bob Dylan had Suze Rotolo, a fellow free spirit whom he called “the most erotic thing I’d ever seen. She was fair-skinned and golden-haired, full blooded Italian. We started talking and my heart started to spin.”

As the recent deaths of 1950s Beat Poets Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Diane Di Prima attest, Italian Americans were no strangers to the protest movements and musical revolutions of post-Eisenhower America. Rotolo was cut from the same free-thinking cloth, a counter-culture child who sought to improve the world.

Although Rotolo is interviewed in Martin Scorsese’s 2005 documentary about Dylan (No Direction Home), her influence on him – both as a songwriter and as a human being – has never been fully revealed. Even in her 2008 autobiography, A Freewheelin’ Time: A Memoir of Greenwich Village in the Sixties, Rotolo, in true modest Italian fashion, downplays her relationship with Dylan, preferring to honor her own personal life journey.

According to a February 28, 2011 article by Richard Williams in The Guardian newspaper (London), written a few weeks after Rotolo’s death from lung cancer at 68 years old, it was quite an interesting ride. Rotolo’s three-year affair with Dylan changed him more than it did her.

Susan Rotolo (she later changed it to Suze) was the daughter of progressive 1950s parents Gioacchino, an illustrator and union organizer, and Marie, a columnist with L’Unita, a Communist newspaper. Her older sister, Carla, was an assistant to Alan Lomax, the famous ethnographer. Rotolo and Dylan met at a folk concert in 1961, moved in together in 1962, and remained a couple until 1964. The only hiatus in their relationship was a six-month sojourn by Rotolo to study art in Italy, referenced in some of Dylan’s songs of the period such as Tomorrow is A Long Time.

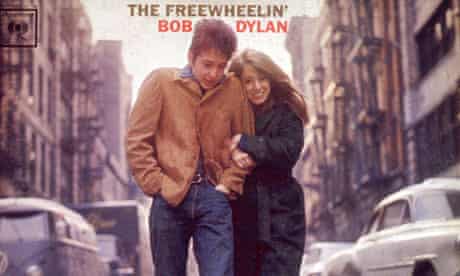

Rotolo was no passive partner to Dylan. According to William’s article, she broadened his horizons via poetry (Arthur Rimbaud), folk music (Woody Guthrie), art (Paul Cezanne), theater (Bertolt Brecht) and social justice (the Emmett Till case). Her gift for sketching, inherited from her father, also inspired Dylan’s visual curiosity. The album cover of 1963’s The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, with a young Dylan and Rotolo walking arm-in-arm in Greenwich Village, is as evocative of its time as the black-and-white photo of actor James Dean walking in a rain-drenched Paris is of the 1950s.

But, the times, they did a-change. In 1964, the Free Speech Movement in Berkeley, California, led by Mario Savio, sparked a cry for social change that our nation is still grappling with. That same year, Dylan and Rotolo went their separate ways: Dylan to fame and fortune, Rotolo back to Italy, where she met and married Enzo Bartoccioli, a film editor who worked for the United Nations when the couple returned to the States.

A progressive to the end, Rotolo protested at the 2004 Republican National Convention and was also part of the satirical theater group, Billionaires For Bush.

Dylan and Rotolo kept in touch occasionally. A quote from her in William’s obituary/article is almost as poetic as a Bob Dylan song lyric:

“(Listening to Dylan’s music), I recognize things. It’s like looking at a diary. It brings it all back. And what’s hard is that you remember being unsure of how life was going to go—his life, mine, anybody’s. From the perspective of an older person looking back, you enjoy the songs. But, you also think of them as the pain of youth, the loneliness and struggle that youth is, or can be.”

In 2019, Nick Broomfield’s documentary Nick and Marianne highlighted the relationship between another gifted Jewish songwriter, the late (Canadian) Leonard Cohen, and his muse, Marianne Ihlen, a Norwegian free spirit with whom he shared a home on the Greek island of Hydra in the 60s and 70s.

Here’s hoping that, someday, someone will likewise crystalize the merging of America’s musical poet with an Italian American woman who, like her ancestral sisters, inspired a talented man to greatness. – BDC

Recent Comments