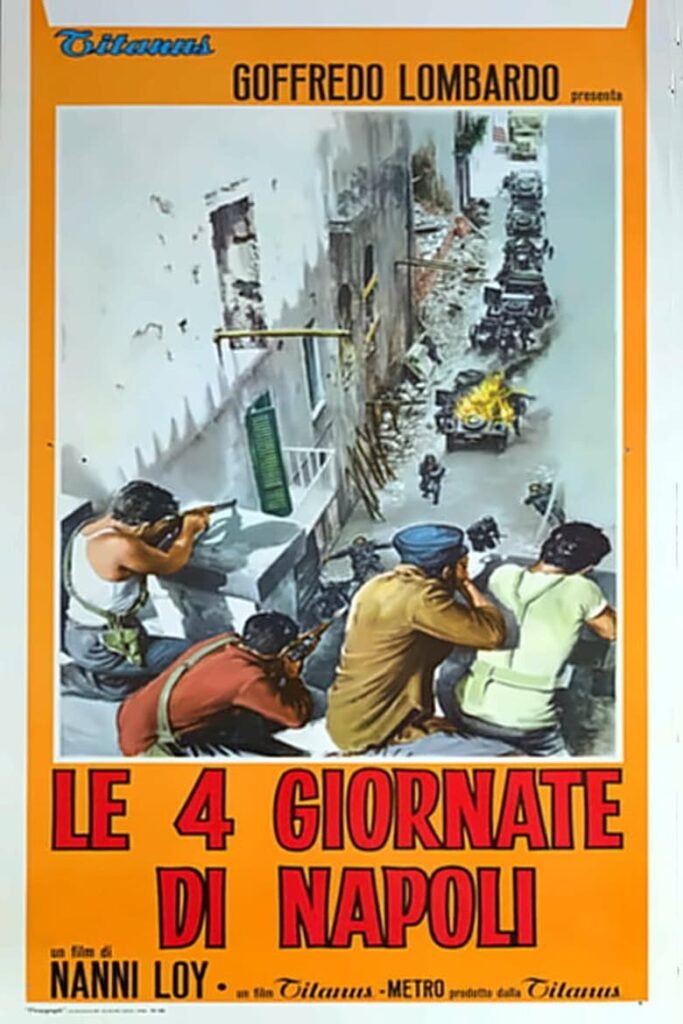

Turner Classic Movies (TCM) recent showed the 1962 Italian film The Four Days of Naples, the true story of the Neapolitan uprising against German occupation in 1943.

I had seen it as a teenager at a Brooklyn theater when it first came out. It was one of the building blocks that formed my italianità. It dramatized an event rarely known to American audiences that had lived through the Second World War, or to my generation that was inculcated with every aspect of the war by way of movies, documentaries, and family histories.

Fascist Italy was a founding member of the infamous Axis, but American movies made during the war portrayed Italian soldiers as victims of Fascism, either being unwilling, unwarlike or just war-weary. I recall A Walk in the Sun (1945), Five Graves to Cairo (1944), Sahara (1943), Immortal Sergeant (1943), Bell for Adano (1945), even Casablanca (1942) all featured hapless or buffoonish Italian soldiers. These movies were televised for decades after the war and watched by millions of American boys who vicariously relived their parents’ war. For any Italian American kid paying attention the message was plain: Italy was not a serious contender.

Jokes followed, some amusing, others cruel: ‘Italian tanks had one forward gear and three reverse’, ‘to make an Italian non-violent put him in a uniform’, ‘the new Italian Navy has glass-bottom boats to see the old Italian Navy’.

On September 8, 1943, after the overthrow of Mussolini and the fall of Sicily, the new Italian government surrendered to the Allies. The Italian military was given confusing orders as to their new mission and how to treat their former German allies. The botched surrender effectively destroyed military discipline and whole units dissolved leaving soldiers to fend for themselves, many just shedding their uniforms and heading for home. Hitler immediately sent an army into the peninsula. On September 9th, the Allies invaded the beaches of Salerno, just 37 miles from Naples, a city now occupied by the Germans.

The Germans considered all Italians traitors and began rounding up Neapolitan men, including newly deserted soldiers, for shipment to German prisons and factories. The Four Days of Naples begins at this point. As soon as the Neapolitans came to realize that “surrender” only meant having a new enemy they resisted deportation. The women of Naples were the catalyst. Having given up their young husbands and sons to military service for three years, they were now losing men of all ages to the ruthless Germans. Their anger and cries spur the men to action.

Soon, ex-soldiers retrieve their weapons and ambush German units. When five Germans are killed in a firefight, the German commandant orders Neapolitan men trucked to a stadium for summary execution: ten Italians for each of the dead Germans. Just as the firing squad is about to shoot, armed Neapolitans in the stadium bleachers unleash a volley on the would-be executioners. From the stadium, all of Naples takes up the rebellion.

German reinforcements making their way down narrow Neapolitan alleys are blocked by armed Italians while the residents of the apartments above bombard them with furniture – including kitchen sinks and commodes. Former soldiers capture a German artillery piece and instruct the older men in its effective use against tanks. Even the reform school kids join the ranks as do Neapolitan children of all ages. Many die, but many Germans too.

Eventually, the Germans have had enough and negotiate a retreat with the Neapolitans. The Allies are still some miles away and no help from them is documented in the film. Naples was not “liberated” by the Allies, it freed itself.

One is reminded of the Warsaw uprising later in 1944 when the Poles rose up as allied Soviet troops watched idly by. The Poles failed and were crushed. From the Neapolitan insurrection, Italy’s agony was only beginning.

The Four Days of Naples covers all the human virtues and vices, with some gallows humor that only the cynical Italian mind could express. But what the film documents should make us all proud. -JLM

The Four Days of Naples can still be seen on YouTube. A number of Italian movies have also been made about the role of Italian Partisans during WWII, which was very effective and very heroic (given that, if captured by the Germans, they would be immediately executed). No wonder that those former Partisans were so offended by Spike Lee’s movie, The Secret of St. Anna.

I just want to point out that Naples and Matera were liberated by civilians, not by left-wing partisans. Naples events do not fall under the left-wing rhetoric of Resistenza. Such events have in fact been dismissed by left-wing historians.

Good point, I’m sure Mario will agree. There were many partisan groups, more than a few were bogus and were denounced by the Italian Republic after the war. British author Max Hastings (The Secret War, HarperCollins, p.27), writes that the Communists foresaw a revolution after the defeat of Fascism. He quoted an OSS report stating that of all the partisan groups the operative worked with in northwest Italy “20 per cent [were] for Liberation and 80 per cent [were] for Russia. We soon found that they were burying the German arms they had captured.”

Yes, as is clear from the movie, a popular uprising freed Naples from the Germans, which took tremendous courage because of the potential reprisals. The Poles also tried to do the same thing in Warsaw but were not successful and many died or were subsequently executed. Thanks for clarifying the point about the great Communist presence in the Partisan movement. I was not aware of that.