Another John Cabot anniversary is upon us—that fateful landing on Newfoundland on June 24, 1497. It was the ‘discovery’ and claim that launched England’s empire and the reason we speak English.

I have written often of this event and how Benjamin Franklin cited it in a 1775 appeal to the British Parliament, to wit: Cabot paid for the journey himself and not then-King Henry VII. Therefore, British taxation was negotiable. We know how that worked out!

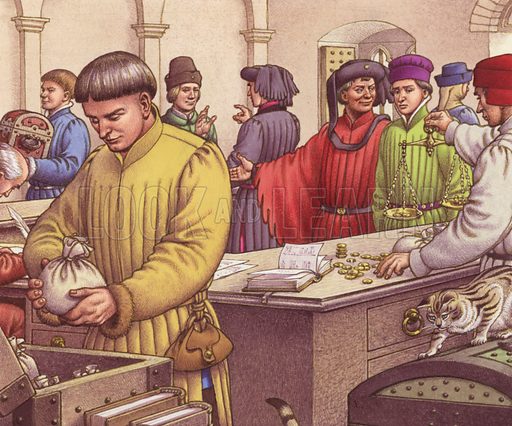

double-entry bookkeeping

Last year, I wrote of a historian who found a ledger in Florence showing that an Italian bank (the Bardi firm) had contributed to Cabot’s voyages from Bristol, England. Likewise, we have proof that Columbus’s voyages were partly funded by Italian bankers in Seville, Spain. Such revelations open up a whole new perspective on the Age of Exploration—who financed the ships and fleets that unified the globe? Why were Europeans the ones who invested the money and braved the unknown? The Chinese were richer; the Muslims were raking in the gold from Asian trade routes. In fact, a Chinese emperor just before Columbus had built a grand fleet to explore the coasts of Asia and Africa (1403-1433) only to recall it when it found nothing of interest. Only an emperor could finance such a venture.

The Europeans had an advantage the others didn’t have: capitalism – an established system of international banking, private financing and shared risk. Such a system was already in place during the Roman Empire when business needed to be transacted among 80 million subjects of differing ethnicities. It was preserved and perfected during the Middle Ages by Italian entrepreneurs in Florence, Siena, Venice, Genoa, and Lucca. Potential clients were everywhere. The Catholic Church needed agents across Europe to collect tithes and pay clergy. European kings required loans to carry out their wars. Wealthy people needed ways to transmit money and to deal with exchange rates without moving gold over dangerous and bandit-ridden roads.

Popular histories would have us believe that only Jews dominated finance and could charge interest on loans in those days. In truth, Italian Christian banks charged interest on loans, as high as 15% to the English. One Siena bank financed the French occupation of Sicily. The same bank went bust when another French king confiscated its assets. What goes around comes around!

Before 1492, Italian banks took in money from Italian monopolies in the Mediterranean, especially spices from Asia and alum from the Middle East. Alum is the stuff that keeps dyes from washing off fabrics. Imagine a world where textiles had no color. The English wool industry depended on Italians for dyes and alum. English wool products were processed in Italy and sold in the Middle East by Italians. Even the Pope got in on the action when alum deposits were discovered in Tolfa, near Rome.

Now the big picture: cash-rich Italian banks and entrepreneurs had offices in every European country ready to invest in a promising venture. They were especially attracted to ventures developed by fellow ‘Italians,’ men like Cristoforo Colombo, Giovanni Caboto, Amerigo Vespucci, and Giovanni da Verrazzano. They knew their family reputations, they had referrals from the homeland, they shared the same culture and Roman heritage. This then was the trade secret of Exploration. These were men you can trust, worth the risk.

Neither Spain nor England would sponsor Columbus or Cabot unless their fellow countrymen put up earnest money. In short, history depended on Italian money. -JLM

Your article is a reminder too, of how complex history really is….and why we need to seek out these “history lessons” because sadly not much of this information is even discussed at the high school level, and rarely even at the college level. What we are getting are simplistic tales, and black and white –good guys , bad guys scenarios…when there is so many shade of grays and other colors too.

On one level telling all these tales are just what they are, but when it gets crazy making is when politicians et al, start to make policy based on these myths…and when you try to point up some of the realities of the historic times, they seem to go deaf or even worst–as I experienced during my Columbus statue days!

As you pointed out while the nation state system was evolving in Europe, trade some how always survived…my favorite, history back story is the well known Scotch J & B. The “J” standing for Giacomo Justerini from Bologna., who in 1749 invested in a spirit enterprise in London that later became the famous Scotch Brand. One doesn’t always associate Italy with Scotch whiskey but where there is a buck there is a way….Happy Caboto Day!