Before there was an Italic Institute I had fun with an imaginary organization named Istituto di Past’Asciutta (ah-SHOO-tah). The name was even fun to pronounce, try it! Literally the Institute of “dried paste,” the term covered all your boxed or bagged macaroni. (The opposite term is pasta fresca, meaning dough usually made with raw eggs and needed to be refrigerated.)

The mission of my ‘institute’ was to standardize the whole macaroni industry. Those were the days before macaroni boxes had cooking times. Remember how many times your mother asked you or your father to taste the boiling pasta to achieve al dente? It was serious business with serious consequences if the macaroni ended up mushy like Chef Boyardee. Now, all pasta boxes have cooking times. Don’t credit my institute. I believe it improved when genuine Italian pastas like Barilla flooded the American market.

Ronzoni and Prince were the domestic brands that we grew up with. There wasn’t much variety in our past’asciutta back then, mostly ziti, rigatoni, and spaghetti. We all called it macaroni or spaghetti back then, not pasta. The actual word for non-spaghetti in Italian is maccheroni. And, the macaroni was usually smooth not grooved (rigati) to better hold the sauce. Today, I buy only rigati macaroni and spaghetti.

I recall my step-mother who arrived here in the 1950s always used Buitoni a popular Italian brand she luckily found in a Brooklyn salumeria (deli). It too was a smooth ziti or penne. One thing I noticed immediately was that her sauce was thin and barely enough to coat the macaroni, no doubt a regional preference quite different from my Neapolitan family. Even her lasagna was made without chopped meat, which I believe is an Italian American additive.

Another goal my institute had was to standardize the thickness of macaroni among the various manufacturers so you could mix different brands of ziti or spaghetti and cook them the same length of time. Got half a box of Barilla penne and half a Luigi Vitelli but one pot? You need to compute the time difference before adding the faster cooking one last. Don’t we have better things to do with our time?

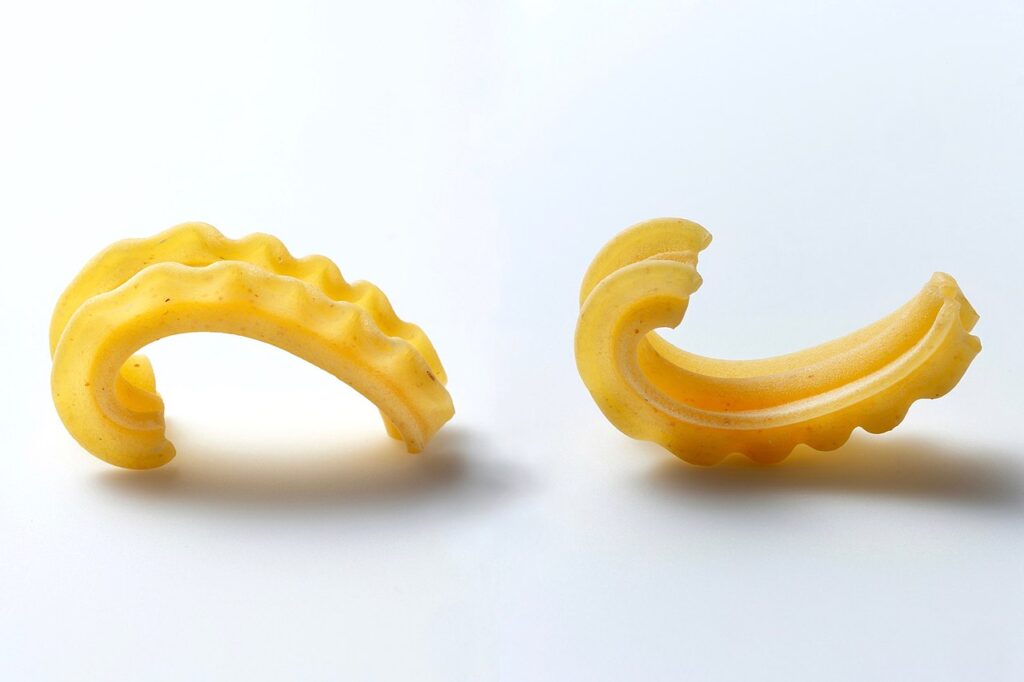

The other major change in past’asciutta is the fantastic variety of shapes – one for every taste and occasion. If the Chinese ‘invented’ noodles they didn’t perfect them – lo mein or dumplings is about all that a billion Chinese have to offer today. Italians have given us one for every day of the year. I am old enough to remember the birth of radiatori at a 9th Avenue, Manhattan pasta store in the 1970s – sadly, I still haven’t tasted any.

Last May, a writer named Dan Pashman in the Wall Street Journal explained how he invented cascatelli, “little waterfalls”- a short curved ribbon with ruffles on each side. Give him credit for reimagining the traditional Italian malfaldine – a long ribbon with ruffles. Essentially, Pashman converted fettucine into macaroni. Goes to show you, pasta has endless pastabilities.

His article also set me wise on other pasta history. Pasta was mainly a southern Italian staple until the reunification of Italy in 1861. The new Italian government built pasta factories in the north to unify Italian eating habits. Mussolini’s “Battle for Wheat” in the 1920s and 30s amplified the drive to unite Italians with more wheat-based pasta. Polenta (from corn) is still a northern staple but scratch any Italian and you’ll find pasta.

Another revelation is that (Spaghetti) Carbonara, a staple of Rome and Lazio, didn’t come from charcoal workers in the 19th Century. Rather, it came with American troops occupying Rome. Bacon and eggs were their main breakfast food and Army mess halls had plenty. Italian chefs adopted the ingredients and after a plethora of combinations since the war, Carbonara was standardized by Roman chefs some 30 years ago with cured pork cheeks, Romano cheese, black pepper and eggs.

I still have a lot to learn about pasta. Maybe I shouldn’t be in charge of the Dried Paste Institute. -JLM

“Pastabilities.” Nice.

Also: Great point about Italic creativity via endless pasta shapes. Art is in the Italic DNA.

My favorite is tortellini, which is based on the shape of (Botticelli’s) Venus’s belly button.

I don’t know about the shapes, but I would be negligent about not pointing out on behalf of my many friends from Trabia ,Sicily (there are more people in San Jose from Trabia than in Trabia itself today), and their claim that Pasta Asciutta, was invented in medieval Trabia. I have no idea, but I am always reminded of it….And regarding “pasta phobia” we could invent another dish, …..a comical side of the Futurist, and there were many, was its attempt to restrict pasta use…..for very strange reasons…needless to say they lost the battle….Unfortunate I missed the event but Il Museo Italo Americano in SF tried to replicate a Futurist recommend meal……a strange one indeed.

It would be remiss in any discussion of pasta to neglect the number system they had across the board for each type. My uncle’s family when we called them to ask about the sacrosanct Italian Sunday lunch and they were preparing spaghetti would only say, “Number 8’s”

John thank you for your lighthearted yet informative blog on pasta. If you return to Rome you should visit the Museo Nazionale delle Paste Alimentari (National Museum of Pasta). You should also indulge in a plate of pasta made with the strozzapreti ( priest strangler) shape!!!

Buon appetito!

The Museo in Rome is another thing I didn’t know about, thanks. Italians are very down to earth when it comes to naming pastas: strings, worms, screws, etc. as well as ‘priest stranglers’ – compare this to Chinese inflated names like ‘Heavenly Chicken’ or ‘Buddha’s Delight’