In the 1987 film Matewan, based on a true story in 1920s West Virginia, filmmaker John Sayles dramatizes the stand-off between corrupt factory bosses and the coal miners whom they exploited: poor whites (Appalachians, largely of Anglo or Scottish stock), African Americans, and Italian Americans. Yes, you read that correctly: Italian Americans.

Italians in the Deep South?

Again, yes, and deep in both senses—a long history there as well as breadth of achievements. In fact, the subject of Italians in coal mining—as with Italians in baseball—could make an entire documentary. The Italians engaged in this dangerous line of work not only in West Virginia but in other coal-rich states such as Illinois, Colorado and Wyoming. Take that, Godfather lovers.

(Note: It was in New Orleans in 1891, during the infamous Hennessey incident, when the very word “mafia” was introduced into the American lexicon via sensationalist news reporting.)

I was in Boston a month ago and am now in West Virginia, a state which opted to separate from Confederate Virginia during the Civil War in1863. The tenth-smallest state, with a population of just under 2 million, West Virginia’s state motto is taken from the language of our classical ancestors, the Romans. In Latin, it reads Montani Semper Liberi (“Mountaineers are Always Free”). Protected by a swath of valleys and trees, West Virginians have maintained this fierce sense of independence ever since.

A famous son of the “Mountain State,” the late Senator Robert Byrd, who still holds the record for longest serving U.S. Senator (51 years!), loved to pepper his speeches with references to classical Rome. Unlike a great majority of Americans, Italian or otherwise, Byrd was well aware of how deeply our Founding Fathers turned to Italic sources via the foundations of our nation. And although Byrd may have been an early organizer of the Ku Klux Klan (a fact omitted in a glowing exhibit about him in the West Virginia State Museum), he rejected segregation and racism later in his career—a sense of justice surely derived from his deep knowledge of Roman history.

(For any readers wondering why I mentioned Byrd’s KKK affiliation, I am engaging in gratuitous fair play: Doesn’t our media automatically try and “connect” any Italian American, regardless of their professions or economic level or achievements, to “the mafia?” As they say in the South, “They do indeed.”)

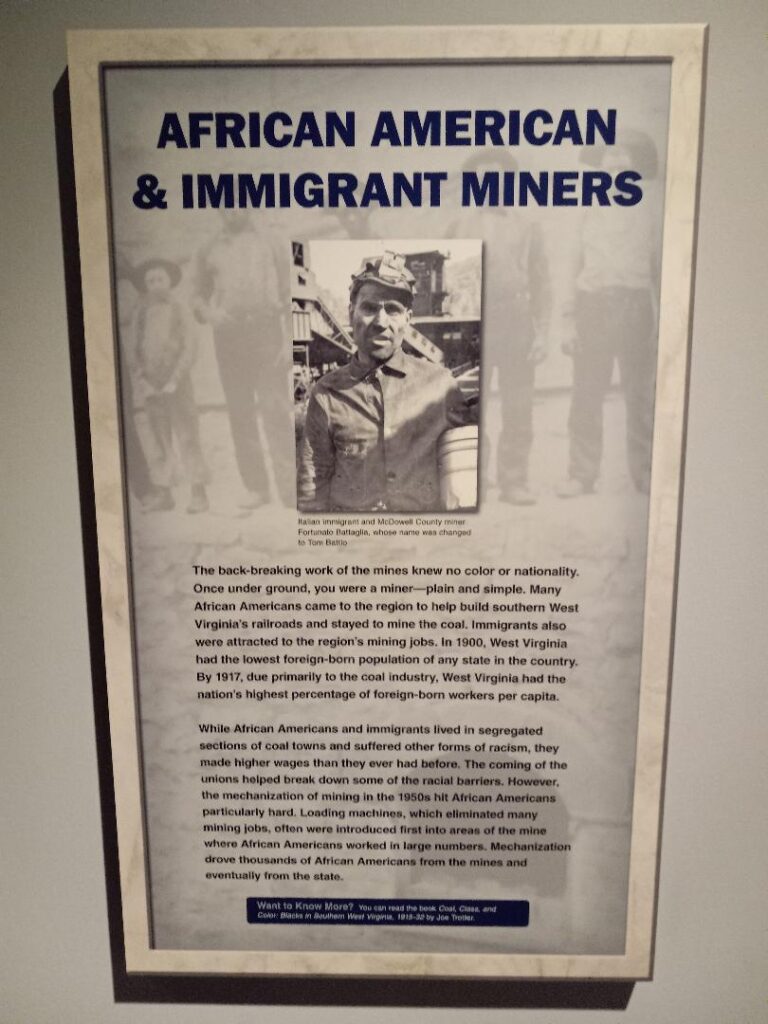

While touring the state museum, I was pleased to discover that the history of Italians in West Virginia is duly documented, particularly via coal mining. There was also a note card and display referencing Peter Gentile, an Italian immigrant whose glass-making company has been around for nearly a century. Ditto various Italian festivals throughout the state.

Likewise, A. (for Antonio) James Manchin is shown in a picture during his tenure as state director of the federal Farmers Home Administration, appointed by President JFK. He later went on to be elected Secretary of State. Alas, he resigned his post in 1989 after he was about to be impeached for allegedly mismanaging state investments. If the name “Manchin” rings a bell, it should: A. James Manchin was the uncle of Joe Manchin, former Senator and governor of West Virginia and an almost-candidate for president in 2024. (Family surname: Mancini.)

Being in coal country, I had to take a coal mining tour. I did so in Beckley, about an hour’s drive from the state capital of Charleston. The tour guide was straight out of Dickens—a chubby, garrulous, retired ex-coal miner in his 70s. His West Virginia accent was so thick I had to surreptitiously “translate” words and phrases for a young German couple sitting next to me on the tram. The couple understood English—but not this English!

At one point, the guide asked us if we knew what pepperoni rolls were. He was shocked when I was the only tourist to raise a hand. Here is a description about them from a December 3rd, 2010 New York Times piece:

The pepperoni roll was first sold by Giuseppe “Joseph” Argiro at the Country Club Bakery in Fairmont, West Virginia, in 1927. The rolls originated as a lunch option for the coal miners of north-central West Virginia in the first half of the 20th century. Pepperoni rolls do not need to be refrigerated for storage and could readily be packed for lunch by miners. Pepperoni and other Italian foods became popular in north-central West Virginia in the early 20th century, when the booming mines and railroads attracted many immigrants from Italy.

The Italians shared them with fellow coal miners, of course, hence their popularity. Pepperoni rolls are now a staple of West Virginia food culture.

What? Italians and food? To quote Gomer Pyle from the old TV show: “Surprise, surprise, surprise.” But food crumbs are better than nothing. I’ll take them. If nothing else, pepperoni sticks rather symbolize both Italic ingenuity and, as per their popularity, our inherently generous nature. And they do lead to a connective discussion of Italian Americans in the coal industry.

“Almost Heaven” is how the locals refer to their state. Italians know a thing or two about paradise. Ask Dante. And they brought some of that vision with them to West Virginia. -BDC

thanks Bill for a fascinating slice of Italian American History….and reminded me of a now friend, who came from Rimini, to Pennsylvania, West Virginia and then to San Jose to track her Italian roots. Many Italians were recruited to work in the mines, and then dispersed throughout the region, some went back to Italy and some relocated in other parts of the USA starting new families so, family members in Italy curious about their families and relatives sometimes have to come to the USA to try to track their family history, all part of the dynamics of the diaspora, and this is what a friend did, and wrote a book about it, bilingual too……..

Precious, just precious.

An example of the automatic reference to the Mafia is this CNN article about the G7 conference in Puglia. https://www.cnn.com/2024/06/11/europe/g7-summit-italy-puglia-security-intl-cmd/index.html. The article erroneously states that the city of Foggia is the epicenter of Puglia organized crime (which tells you that these articles are really to disparage Italy and nothing else).

However, I wish it was just the media that systematically connects Italians to the Mafia. It happens in real life too.

An Italian man, Chico Forti, just returned to Italy after spending 25 years in a Florida penitentiary. He is from the Alpine northern region of Trentino and he was a windsurf champion.

Apparently, the investigators and prosecutors brought up absurd Mafia connections.

Imagine the power of such allegations when presented in front of the average American juror.

Kind comments. Thanks.

I forgot to mention that there’s a very fine, very large statue outside of the Clay Center for the Arts in downtown Charleston, WV—it shows a group of characters in “Commedia dell’arte” costumes marching around a maypole. It was done with rock imported from Pietrasanta, Italy. Not sure why it’s there but it was a pleasant shock.

Just read your comments about Puglia. Totally agree.

Mexico just elected its first female leader. Hosannahs in the press. It took the American media at least 6 months to even mention Giorgia Meloni’s existence.

To my main point: Another female Mexican leader (mayor of a town) was assassinated ON THE SAME DAY as Ms. Claudia Scheinbaum’s victory. Nary a peep in the press about the assassinated leader, nor the prevalence of violent narco gangs.